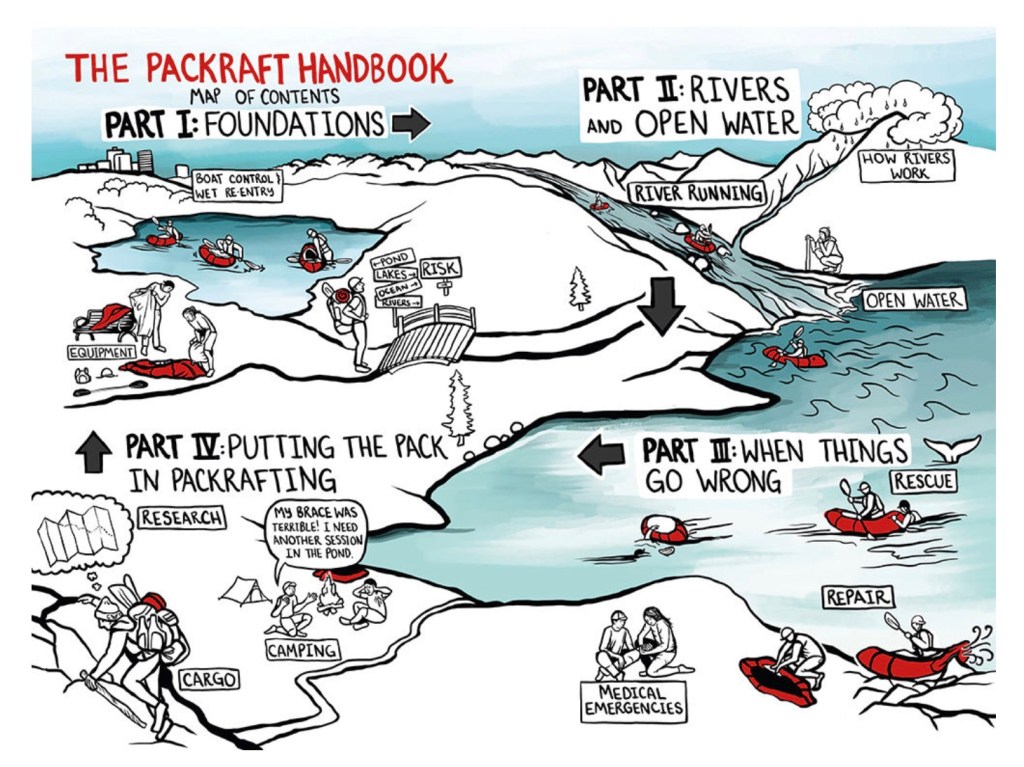

Are there really 450 pages to write about packrafting? Let’s find out!

In a line

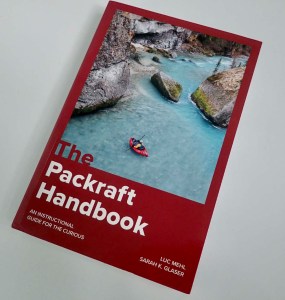

You’ll learn more than you’ll ever use from this lavishly illustrated handbook, with loads of safety advice that focuses strongly on the author’s preference for whitewater.

• Presented with an engaging humility and humour which helps deliver important messages

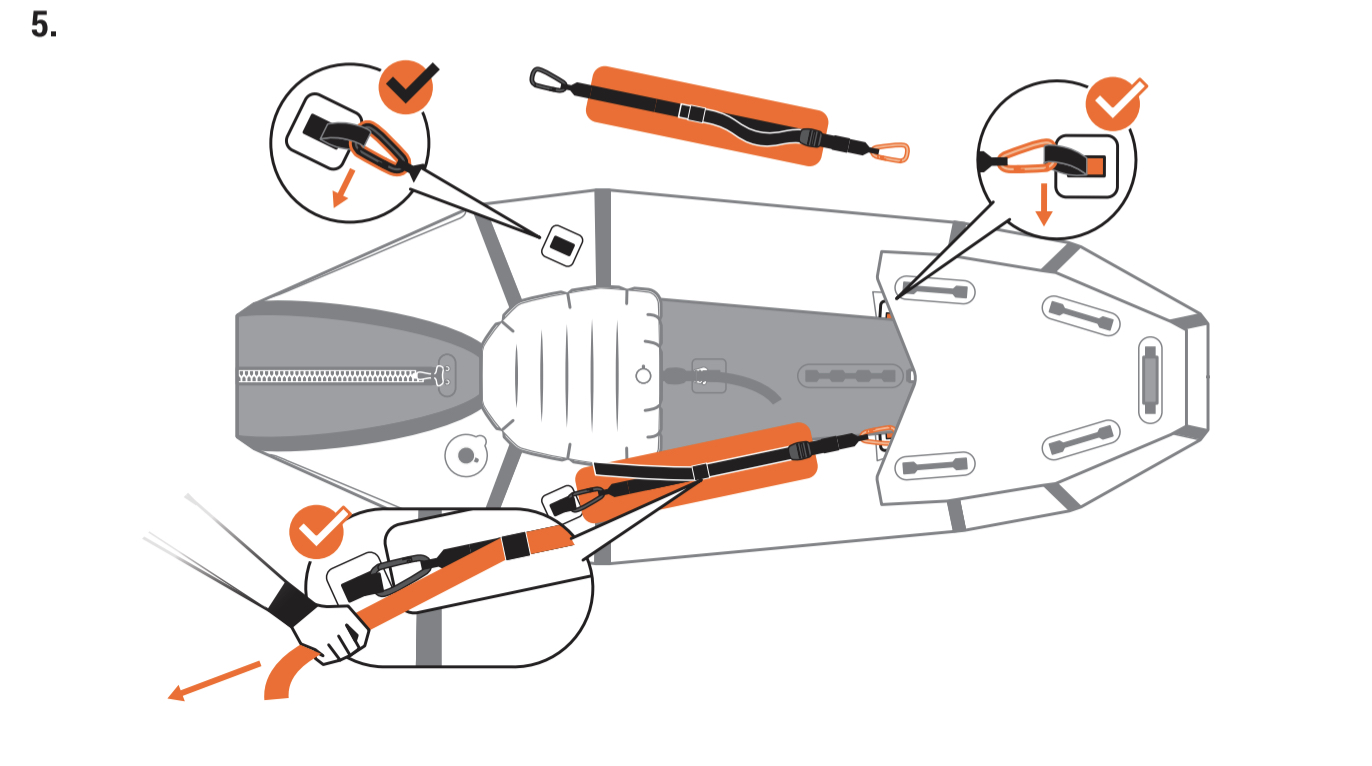

• Sarah Glaser’s vibrant graphics often work better than photos

• Goes from £26 on amazon

• Like the best handbooks, even the experienced will learn something new

• For a 450-page handbook on packrafting there are some odd omissions: no words or pictures about crossrafts or tandem paddling, sailing, bikerafting (bar one loading graphic), even packraft ski-ing which sounds fun and the author seems to have done

• Like similar kayaking books I read ages ago, it can all feel a bit off-putting – which may be a good thing

• Inevitably, Alpacka and Alasko-centric, a magical if unforgiving wilderness with unique challenges.

What they say

The Packraft Handbook is a comprehensive guide to packrafting, with a strong emphasis on skill progression and safety. Readers will learn to maneuver through river features and open water, mitigate risk with trip planning and boat control, and how to react when things go wrong. Beginners will find everything they need to know to get started – from packraft care to proper paddling position as well as what to wear and how to communicate.

Illustrated for visual learners and featuring stunning photography, The Packraft Handbook has something to offer all packrafters and other whitewater sports enthusiasts.

* This review refers to the original 2021, Canada-printed edition self-published by the author, not the 2022 version published by Mountaineers in Seattle and printed in Korea. There may be small differences in content and print quality.

I recall reading Roman Dial’s Packrafting! (right) when I started out and thinking, Oh, there’s really not much to it provided you avoid churning whitewater. At that stage I’d been into IKs a few years and had read the basics in The Practical Guide to Kayaking and Canoeing, a huge, 256-pager by Brit, Bill Mattos. That book covered everything you can do in hardshells but, being more traveller than thrill-seeker, was instrumental in steering me away from the sort of high-adrenaline antics depicted on both covers.

Wisely, Luc Mehl, an environmental scientist and ‘swiftwater’ paddling instructor, opts for a serene front cover, even if he’s a skilled exponent of whitewater action. His blurb above states: “… packrafters and other whitewater sports enthusiasts” suggests he sees packrafts as whitewater boats you can easily travel with, rather than easily portable boats you can take anywhere. That’s an important distinction.

It was produced in response to the death of a fellow packrafting journeyman, as well as several other tragedies befalling close friends. The book’s tagline has been #CultureOfSafety, as in making it second nature to use the right gear, learn appropriate skills, pick the right conditions and make smart decisions, including scouting and if necessary, portaging sketchy situations.

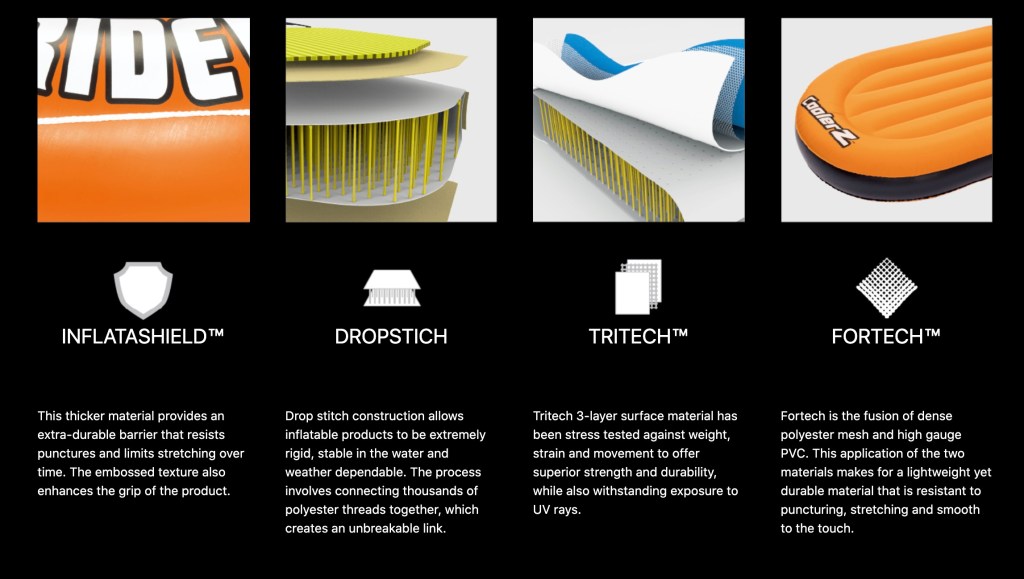

Inside, The Packraft Handbook uses thick, glossy paper to help Sarah Glaser’s graphics jump off the page. As a result it weighs nearly a kilo and must have cost a fortune to print before Mountaineers picked it up in 2022.

Early on, there’s an aside which resonated with me. “Many topics in this book won’t seem relevant until you experience missteps. It is more important to know what is in the book than to understand it all.”

Having written similarly weighty handbooks on other subjects, that’s something I’ve frequently heard from readers: it’s only after having been there and done that, including bad decisions or choices, that they get what the book was telling them all along. This will doubtless be the case with The Packraft Handbook.

Tellingly, Luc Mehl found that kayaking whitewater in hardshells accelerated his skill development much faster than a packraft. Sure, a packraft feels stable but when it flips it does so with little warning, unlike a hardshell creekboat with far superior secondary (‘on edge’) stability. The point, of course, is a packraft is so much easier to carry overland for days at a time that the compromises are worth it. I skimmed over most of the technical whitewater paddle strokes which, as in Bill Mattos’ kayak book, is stuff with little application to the type of packrafting I did then or do now.

Even before you get to page 99, it becomes clear that both Luc Mehl and many of his intrepid contributors who supply pithy, lesson-learning asides, have had several close calls while ascending their packrafting learning curves, mostly in the unforgiving Alaskan wilderness.

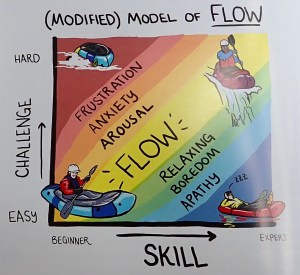

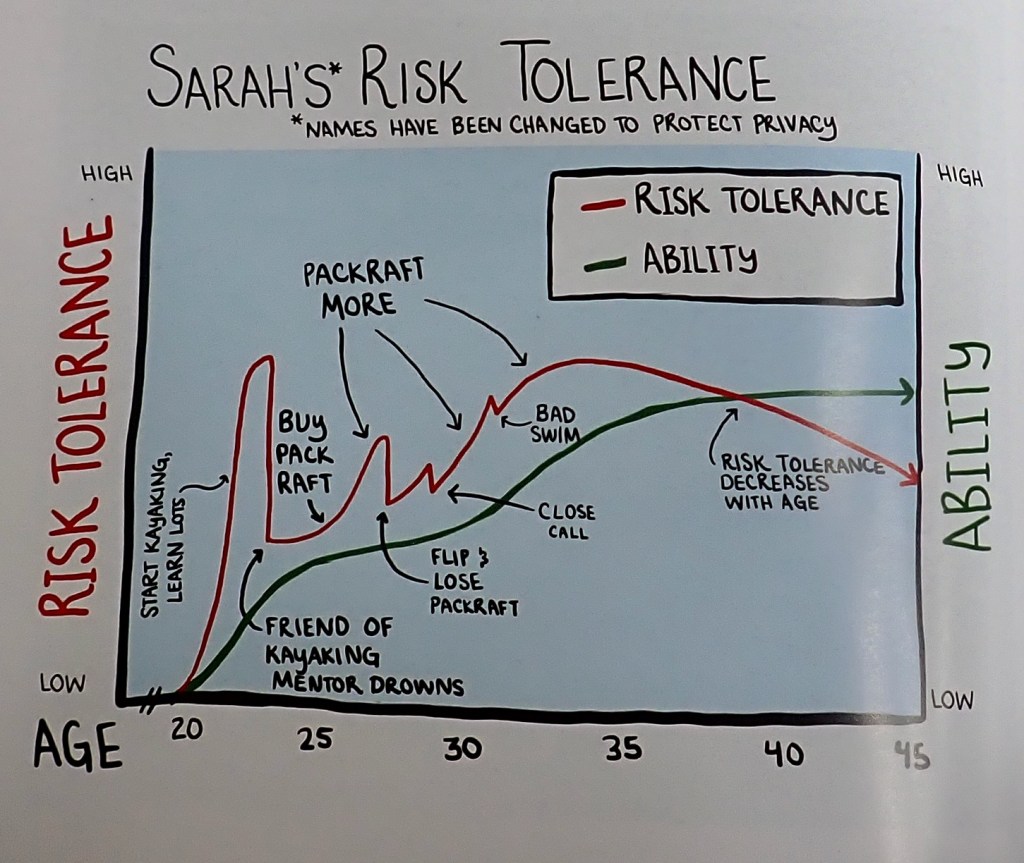

Then you take someone like me who’s never fallen out of a packraft, yet enjoys their amazing potential just the same. Aside from the fact that I live in the opposite of Alaska, one explanation may be the graph (below) featured in an interesting section on risk, ‘safety drift’ and ‘heuristic traps’. We learn that three often repeated words are key to assessing risk: Hazards, your Exposure and subsequent Vulnerability.

Having learned the basics in the Mattos book, I got a bit bogged down in the slightly over-technical How Rivers Work though it was interesting to read that bedrock rapids have a more dangerous character than silt riverbeds, perhaps because they resemble hard-edged, man-made wiers. And, along with the regular inclusion of snappy ‘Pro Tips’, I liked the ‘River as a series of conveyor belts’ graphic analogy – a novel way of explaining the complex flows of rapids.

I have to admit before I was even halfway through I was beginning to skim more and more river-running lore, while enjoying the boxed-out anecdotes which are the gravy in books like this. While I had a familiarly with what was being expounded, aspiring to master nifty river moves is just not what I do. My ability, such as it is, plateaued years ago while my risk tolerance drops by the second. Still, it all needs to be written down and explained in one authoritative source, and all the better from a specifically packrafting viewpoint building on many years experience.

The section on open-water crossings is based on the travels and subsequent material by Bretwood Higman and Erin McKittrick, whose record of their epic journey, A Long Trek Home I read soon after getting my first Alpacka.

I paid a bit more attention here as in Scotland it’s the most exposed packrafting I might do. That section includes the sobering account of a British bikerafter who drowned during a Patagonian lake crossing of just 2km, and where having his boat leashed to his paddle or himself – a massive whitewater no-no – may have saved him.

I’m reminded of another formative book I read ages ago: Sea Kayaking Deep Trouble; US-based analyses of sea padding fatalities and rescues, and crucially, what lessons can be learnt. Luc Mehl curates a webpage of known packraft fatalities which similarly hopes to inform packrafters on how to avoid getting in too deep.

As a result of reading most of this book, I finally did something about a couple of safety and entrapment issues that have been lightly bugging me for years: I ditched a cheap, heavy (and barely used) locking rescue knife for an as-heavy but quick-grab NRS Pilot Knife which at the same time can also replace my never used Benchmark rope-cutter. (Maybe I missed it but, despite the repeated dangers of entrapment, I saw no mention of such knives in the Handbook). And I got round to fixing a reusable ziptie to a bow attachment loop to retain my bunched-up mooring line when on the water. ‘Wayward Lanyard’ a mate called it last weekend. He has all his early LPs.

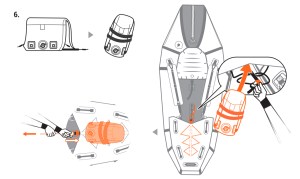

As things get more serious in When Things Go Wrong your attention span may falter in the face of elaborate river-rescue techniques, including rolling your capsized raft (depicted in a series of graphics that make the technique very clear – a first for me), as well as increasingly intricate shore-based rope recoveries which are probably better watched or practised than read about.

Equipment Repair and Modification is a valuable resource of proven recommendations and ideas for tapes, glues and what works best for just about every sort of eventuality. It’s bound to be of use to many. Similar content appears on Luc Mehl’s website.

Medical Emergencies underlines, among other things, the importance of understanding cold-water shock – the reflex which most commonly leads to drowning long before you’ve had a chance to catch hypothermia. Here I also learned something that’s puzzled me: why some drowning survivors still end up dying a few days later: pulmonary edema.

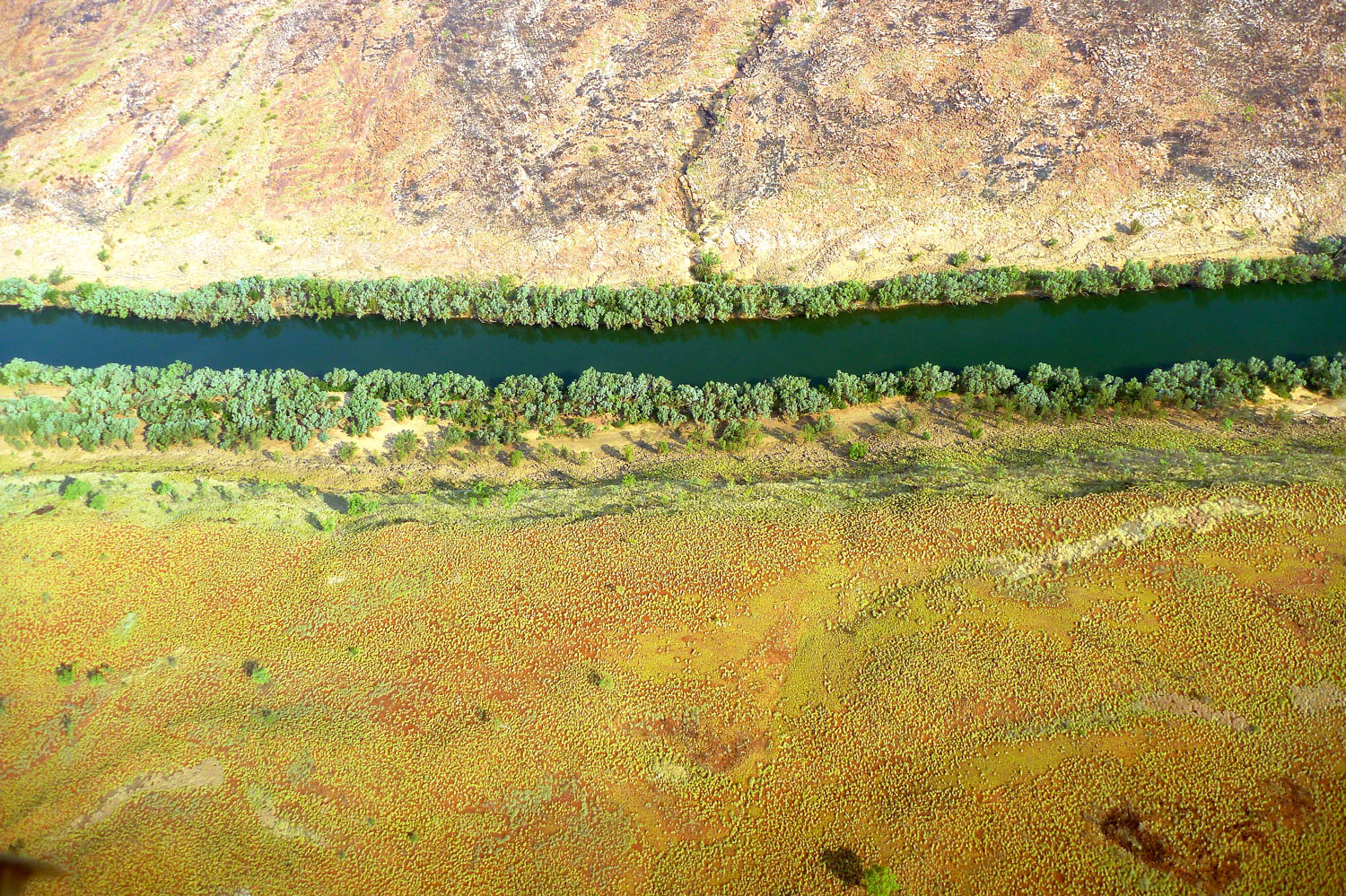

At one point Luc Mehl describes how shooting off waterfalls down in balmy Mexico gave him a new perspective on risk – as in things felt less dangerous in the tropics. I remember thinking the same thing while struggling to kayak along Australia’s Ningaloo Reef. The wind was howling, the waves were annoying, but it all felt a lot less scary than it could have because it was sunny and warm. No risk of cold-water shock here, just being swallowed by a whale shark.

The final two chapters about backpacking gear and trip planning were surprisingly skimpy; a sign of end-of-book syndrome? As it is, backpacking gear choices are highly subjective and are repeated all over the blogosphere (not least here!). The planning chapter felt very Alaska- and river centric (not much about the terrain in between which can be as challenging). But if you can pull off a successful backcountry trip in Alaska, you can probably do so anywhere.

The book ends with no less than 16 pages of glossary and an appendix listing sources and additional resources. Design-wise, I’d say it’s bad form to have short boxed asides rolling over the page – across a spread would have been better. And it’s a shame that all of Sarah Glaser’s graphics (mixed in with some of the author’s?) weren’t in vibrant colour; that would have made a stunning book as it’s a great look which vividly delivered the lessons.

Much as Bill Mattos’ hardshell book helped guide me towards my current packboat interests, a first-time packrafter with big ambitions is bound to value having the thrills and spills of whitewater packrafting laid out in The Packraft Handbook, all the better to decide what sort of packrafting appeals to them.