See also:

Packboating in Southern France

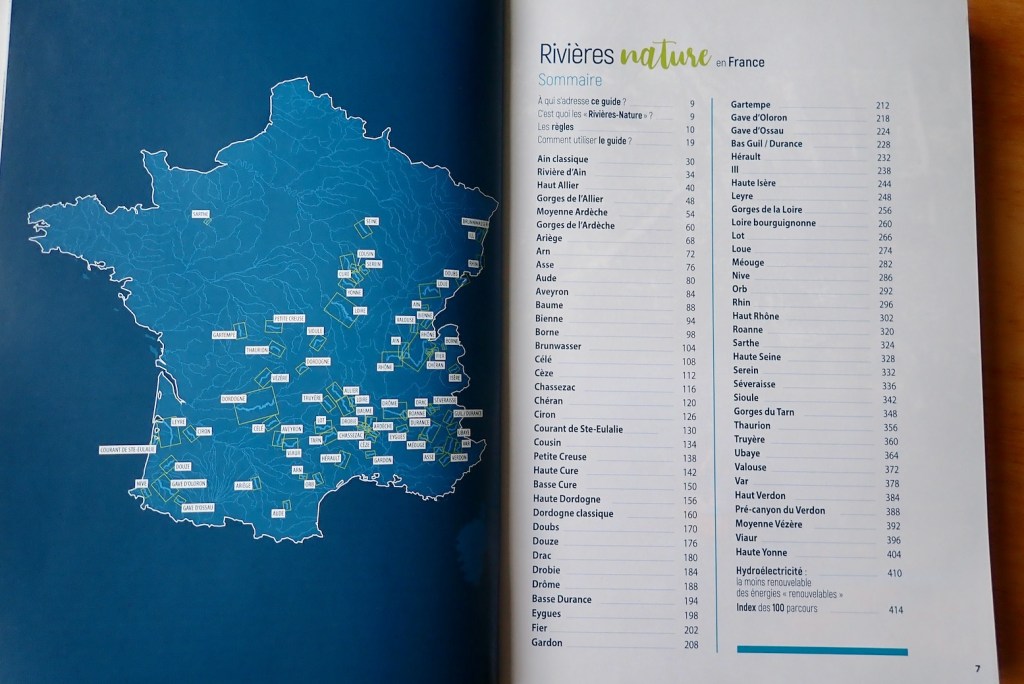

Book review: Rivières Nature en France by Laurent Nicolet

Book review: Best Canoe Trips in the South of France

ISUP: a new way to get in trouble at sea by Gael A

Guardian: Six best Paddles in France by Anna Richards

In a line

Mouthwatering selection of river- lake- and inshore paddles right across France, but packboats go unmentioned, despite lauding the use of public transport.

What they say

This award-winning new Bradt guidebook provides 40 itineraries for water-based exploration around France by SUP kayak & canoe to suit all abilities. It is the first practical guidebook to explore the whole country by SUP (stand-up paddleboard), canoe and kayak – waterborne activities enjoying a popularity boom.

Experienced paddleboarder, travel writer and local resident Anna Richards has toured the country’s rivers, lakes and coasts to handpick 40 outstanding itineraries for water-based exploration that suit all abilities from novice to expert, enabling readers to experience Metropolitan France as never before!

Rrp £19.99. 41 maps, 230pp

Review copy supplied by Bradt Guides. Book images found on online previews.

Additional contextual review info by French boarder, Gael A.

• Varied selection of paddles right across the six corners of l’hexigone and Corsica

• Nicely written descriptions

• Maps are small but routes are short so they do the job

• W3W works well for pinpointing locations

• Nice layout and paper

• Printed in the UK – better sustainability

• Routes appear to be composed almost entirely from set rental/guided itineraries

• Most are short return paddles

• When it comes to paddling knowledge, the author seems out of her depth

• Nearly all photos are stock library shots

• IKs and packrafts virtually unmentioned, yet as transportable as a rolled up iSUP

Review

Thanks to its topography, rich history, culture and proximity to the UK, on river, lake or sea, France is a fantastic paddling destination. Paddling France: 40 Best Places to Explore by SUP, Kayak & Canoe replicates Bradt’s Paddling Britain by Lizzie Carr which, in its first 2018 edition, was a long-running hit, possibly supercharged by lockdowns when demand for inflatables boiled over.

Like many others at this time, author Anna Richards discovered the wonder of paddleboarding, moved to France to become a travel writer and, knowing the country from childhood holidays, zig zagged around for over a year to write and research it all.

Paddling France isn’t aimed at enthusiasts attracted to the challenge of developing skills by juggling tidal streams and winds, river flow rates or the logistics of multi-day tours. Most SUP owners are into casual day paddles, but probably outnumber the former by ten to one.

But unlike Lizzie Carr’s original Paddling Britain (which I checked after writing this), faced with an equally monumental task, in most cases Anna Richards seems to have either rented kayaks (and maybe boards), used their shuttle services, or at sea sometimes joined tours. Although all are great paddles, I didn’t get the impression any routes were original selections born from years of experience, the usual prerequisite for authoring a guide book like this.

Initially I understood ‘… generally with the assistance of local clubs that kindly loaned me rigid… kayaks‘ (page xix) as a euphemism for arranging rental freebies in return for a listing in the book. But it’s possible the author actually believes ‘clubs’ – in the social/membership/lessons UK sense – is the right word to describe a commercial rental, tour and sometimes training outfit. Only Route 21 lists a ‘Club Nautique‘ sailing school which also rents kayaks and boards. All the rest call themselves versions of watersports centres or ‘location canoë-kayak‘ (kayak rentals) of which there are many more in France than in the UK.

Once you get your head around this you ask yourself: well, it’s a short-cut but in France does it actually matter? What are most Brit paddle tourists’ experiences in France? Is it flying or railing down with a packboat, as I’ve done? Or is it driving around with kids or campervan, then chancing upon a lovely waterside spot which offers day rentals and a lift back? It’s almost certainly the latter. That’s what I’ve done elsewhere in the world.

It’s clear the author put in the miles, paddled every route and composed a detailed description and practical info, although images of her in ‘off message’ kayaks are absent, replaced by stock library photos with fill 90% of this book. With mainstream guidebook sales in retreat and corners getting cut, these are all understandable measures to still produce a nicely designed and illustrated book in full colour for just £20 that’s printed in the UK, not the other side of the world. That alone deserves a sustainability rosette which the publisher should laud.

I wouldn’t consider blagging a freebie rental in return for a mention as unethical, as long as it’s clearly flagged. Many routes start and end right outside an outfitter’s base. I could be wrong, but if that’s the case better to be upfront. Skimming through Paddling Britain, that book appears to have been written and researched the old fashioned way – though again, no mention of packboats ;-(

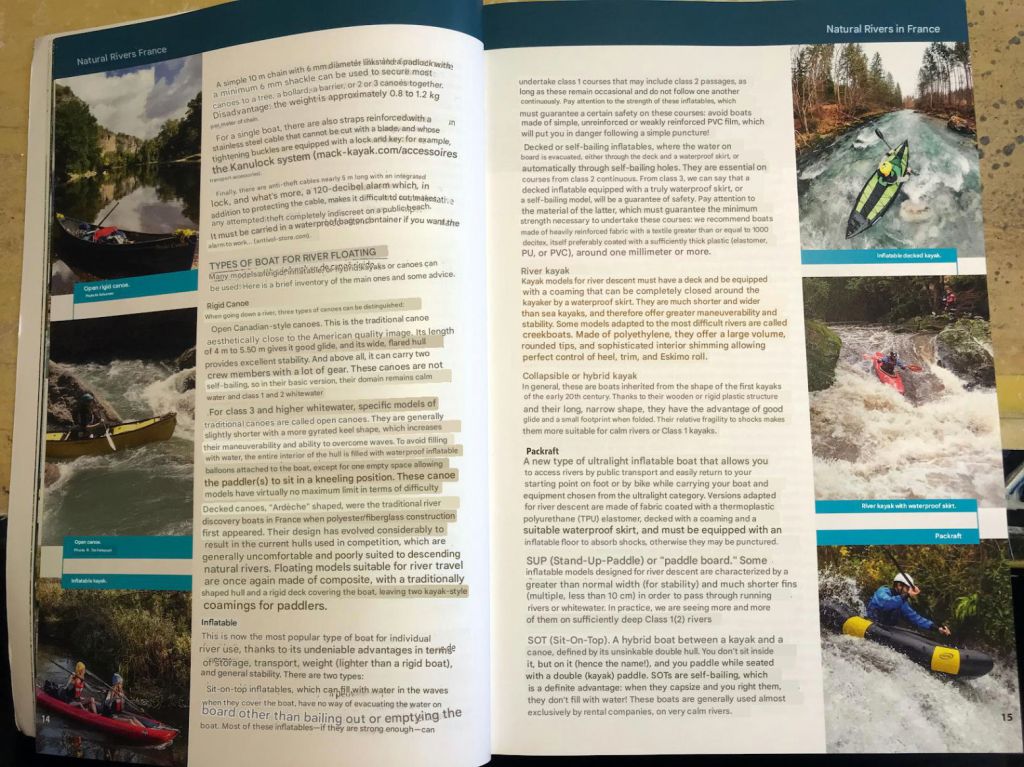

Ironically, Anna Richards likes iSUPs for some of the same reasons we all rate IKs and Packrafts: ease of use and transportability. Yet as said, many routes seem to be in rental hardshells, while IKs get dismissed in the Intro’s second para (left) as too awkward to travel with compared to a SUP.

I looked up what a 12.5′ inflatable paddle board weighs: about the same as a Gumotex Twist 1, and 2-3 times more than a packraft, though I admit a 4-metre FDS IK (above right) is ridiculously bulky. What a shame then she missed out on made-in-France Mekongs packrafts rental service. Some rental outfitters listed even supply Mekongs. On a lively river I’m sure she’d have been thrilled. So, no IK or Ps in this book (bar photo p5), but of course, conditions permitting, all routes are suited to packboating.

The author seems to be more enterprising travel writer with a SUP hobby, than experienced river runner and has a talent for filling out evocative descriptions with not much to go on. For an inspirational as much as practical title like this, that may be a better balance, but it’s a shame we can’t have both. If you’ve used serious paddle guides, Paddling France falls a little short in places.

What I now realise are linguistic mistranslations of French paddling terms jar, suggesting the author was inexperienced in writing an English paddle sports guide that must include accepted terminology and elements of technique, appropriate gear, water hazards and safety regs. Page 16 and 18 excepted, the frequent use of disembark to ‘get off’ [your board/the river] but also to ‘set off’ [for the paddle – p66] get particularly grating. This is a literal translation of a similar French word which doesn’t always work in English. Marinas get described as ‘ports’ or ‘harbours’ or even ‘pleasure boat ports’ – also not the same thing. Nor is a weir a dam in English (though in the US they call them ‘low-head dams’). It took me days to realise this. I now wonder if paddling newb Anna Richards learned her paddling and nautical terminology in French while researching this book, then translated some words literally into English. Hence the odd use of port de plaisance – the clumsy French phrase for marinas. Or assuming barrage translates to dam, weir (or roadblock), when all three are quite different things. As an aside, a few times a SUP board is called a ‘paddle’: ‘inflate your paddle’ roll up your ‘paddle’. Is ‘paddle’ slang for a SUP in French? Probably not*

But then an often-repeated claim dawned on me: English vocabulary is many, many times greater than French or any other language – no wonder L’Académie Française is so defensive ;-) You won’t drown horribly as a result of all this, but if writing a paddle guide in English for English readers, use or learn the right words – or check with someone who does.

- Actually it is! Gael writes: Some years ago the term “paddle” has been inexplicably adopted as the official French word for SUP. Stand Up Paddleboard would translate into something like “planche propulsée en position debout au moyen d’une pagaie”, or PPPDMP which would be difficult to pronounce. Italians called it “tavola da SUP”, which is shorter but nearly as ludicrous.

‘Paddle This Way’

Working through the book, up front after a handy country map which you’ll be referring to a lot, we get 26 (or xxvi) pages of what and how. Flying is discouraged for environmental but also supposedly impractical reasons even if, despite what’s claimed, a packboat or iSUP is easily loaded on a plane. There’s good info on the various car regulations including urban emission restrictions which could catch a foreigner out.

On a Eurostar there’s no weight limit, so if you can get two bags like left (IK with camping gear on a folding trolley) you’ll not pay excess fees, despite what’s said. With a packraft there’s nothing to it.

There follows a section about paddleboarding with the ‘accessibility and flexibility’ words I see mentioned so often, but which have long applied to packboats too, and especially packrafts (sorry; we’ve finished this argument, haven’t we?!). How to SUP, choosing a SUP and washing SUP; it’s all summarised. Kayaks and canoes get slightly less detailed treatment from expert contributors lifted from the Britain book who list elementary turning strokes a child would guess. Better to suggest a technique I found less intuitive: pushing on the upper arm, not yanking on the lower, as so many kayak newbs do.

A box on renting boats and boards (also listed locally after each Route) recommends French outdoor retailer Decathlon’s IK rental service (and which might have included Decathlon’s packraft range, cough, cough). But I couldn’t find any rental boats on decathlon.fr and think that side of the service has been dropped.

Talking about gear, much of it makes sense, but it’s odd to see a manual SUP pump listed as ‘the biggest regret of the project‘, with the advice to get a 12-volt car inflator. So much for using public transport then! You can have both of course – long/thin SUP pumps are bulky compared to pocket packraft inflators, but the autonomy they offer changes the game by being able to ditch cars.

A ‘Wear a Buoyancy Aid’ heading on page xx unfortunately appears right below a stock shot of half a dozen SUPists clad only in skimpy swimwear (and again two pages earlier). I read here 62% of UK ‘boarders don’t regard a PFD is an essential safety item. I rarely see them worn, but then I rarely see SUP boarders actually standing up. I suppose as long as you’re leashed to your board (the skimpies are unleashed), in deep but calm water you can crawl back on, providing you clung to you paddle. But on some of the listed rivers I know a leash can also be an entrapment hazard. Not mentioned. This is where handbooks or guidebooks written by paddling pros like Bill Mattos, Peter Knowles, Mark Rainsley, Laurent Nicholas, Luc Mehl and even Bradt’s own Lizzie Carr and Wild Thing’s Lisa Drewe have the edge. I’ve learned a whole lot from nearly all of them.

To her credit, every photo of Anna Richards on a board is in full wetsuit with pfd. What a shame there was no shot of her on Route 31 in Lyon, her home town – just more stock imagery. River rowers never wear BAs either, but it does seem to be a blind spot with SUP users. As said, most of the book’s images come from photo libraries, and of the SUPs pictured in the book, half have no BA, compared to only 1 in 10 kayakers.

With off-season paddling often covered, you’d think then here’d a good place to mention the perils of cold water shock (scroll down to ‘C’) to drive the PFD message home: you drown flailing in a breathless panic long before succumbing to hypothermia. On Lake Annecy (Route 33) we’re told winter water temps are a ‘distinctly refreshing 4°C‘.

There’s also no mention of the real menace of weirs (barrage in French; ‘low-head dams’ in the US) which led to that Welsh SUP tragedy and was also drummed into my paddle reading early on.

There follows some boilerplate stuff on responsible paddling. Good to learn wild camping in France is a bit less illegal than I’d thought; it just emphasises how satisfying multi-day routes are (as in the Britain book). And I never knew canal paddling wasn’t allowed either*, nor the Seine in Paris. No wonder the French are so militant!

* Gael A adds: Canal paddling is allowed in many places. Inland waterways can be rivers or canals. Those capable of commercial shipping are managed by the public company Voies Navigables de France VNF. VNF decides which type of craft is authorized on each waterway or portion of waterway. For instance the Seine through Paris intra-muros is not allowed to sailing dinghies, skiffs, canoes, SUPs etc., while it is allowed downstream near Boulogne-Billancourt or Maisons-Laffittes and upstream near Saint-Fargeau for instance. VNF manages wide and deep waterways open to large barges. Older narrow gauge canals still in operation like Canal du Midi, Canal de Bourgogne or Canal de Nantes à Brest are no longer used for shipping and from now on dedicated to recreational navigation, which includes recreational barges, river yachts, canoes, SUPs, etc. For instance, when I couldn’t paddle on the river Marne because it was in spate, I went to Canal de l’Ourcq, although canal paddling is boring actually.

Division 240 sea regs

With sea paddling routes included, I’d have expected a reference or at least a link to France’s Division 240 regs and how they might apply to SUPs. Another thing that could catch foreigners out, just as with driving, especially Brits from reg-slack UK. IK&P’s French SUP correspondent Gael A explains the sea regs as follows:

Division 240 applies to SUPs more than 3.50m [11.5′] long.

SUPs shorter than 3.50m fall into the beach toy category, consequently they can’t go beyond 300 m from a sheltered shore.

SUPs longer than 3.50m can go beyond the 300m limit up to 2 nautical miles [3.7km], by daytime only, provided they comply with watertightness, stability and buoyancy requirements described in Division 245.

To make a long story short, a SUP must have 2 chambers. A SUP with only one chamber is considered a beach toy even if longer than 3.50m. Obviously watertightness and stability requirements don’t apply to SUPs.

Navigation in the 300m-2nm zone requires the following safety gear:

• leash

• PFD 50N or wetsuit or drysuit

• waterproof signal light like a strobe or a headlamp, or even a cyalume stick provided it is attached to the PFD.

So my single-chamber, 2.8-m TXL packraft would sadly be demoted to the beach toy it resembles and be restricted to less than 300m from a shore. But just as with having a high viz vest, warning triangle and breathalysers in your car (all detailed on pager xi), you do wonder how- or if all this is enforced. It’s a guidebook’s job to inform readers.

Winds will always be unpredictable but there’s very little tidal information on the salt water routes, and whether it might be a factor. The much loved MagicSeaweed app listed on page xx went offline mid 2023, 10 months before the book was published, and its replacement seems surf based. (There are similar online weather and sea state resources.) Down on the Med tides aren’t a thing, but Brittany has some of the world’s highest tidal ranges, reaching 15 metres on some routes. Not everyone may fully appreciate how if could affect some paddles.

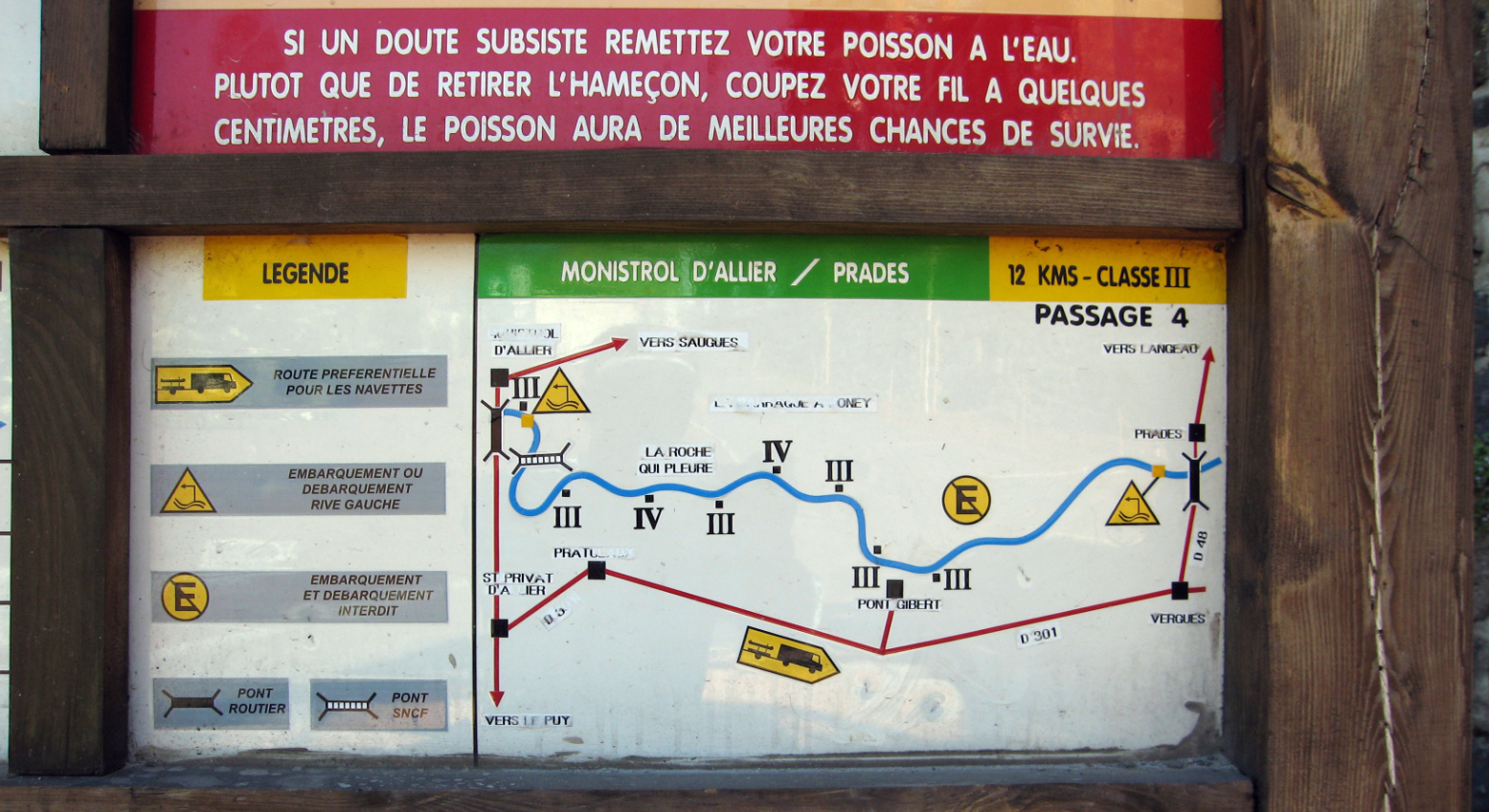

Odd that there’s no mention or imagery of thrilling glissades or passe canoës (canoe chutes, left), a French speciality rarely seen in the UK.

Built especially for paddlers (and sometimes fish) to avoid tedious portaging around weirs, glissades aren’t listed in the Paddling Vocabulary on p222. They’re an added highlight to many rivers I’ve paddled there and you’d think it might be fun to try sat on a SUP too.

Location and nav

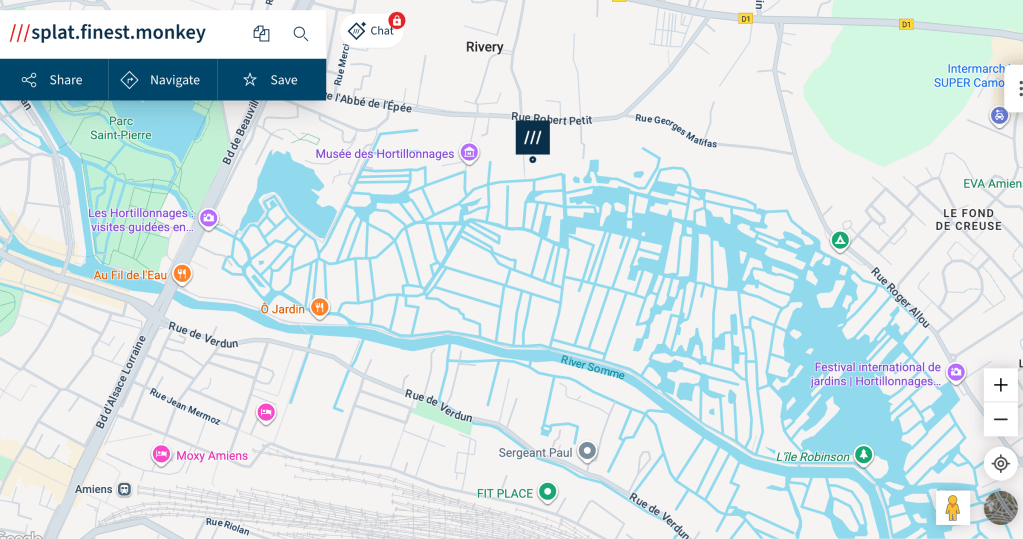

Like some other guidebooks, the Bradt uses the What3Words GPS location app to precisely pin down riverside put-ins as well as passing POIs on third-party mapping. I got into using the W3W website (not the app) to orientate myself with the book’s routes and ///graphics.dads.inched is much easier to momentarily memorise then type correctly than 48.85840, 2.29447, although the Rivières Nature en France guide uses QR codes which go straight to map; no typing needed. Only once on Route 27 did the W3W launch point end up near Tomtor in far eastern Siberia and the coldest settlement on earth. All the others were spot on. The W3W app also provides the conventional numerical D.D° waypoint equivalent (as above) which a GPS device needs, and which will work on all other mapping apps, not just W3W. Both (and QRs) are so much better than the archaic OS grid ref system used in the first edition of Britain as well Pesda guides. The world’s digital now.

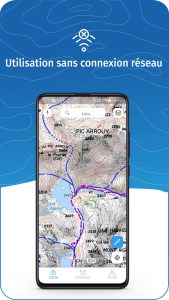

Talking of maps, I’d have expected a tip towards the IGN Rando app, (left) the French equivalent of the UK’s excellent Ordnance Survey. Widely used Open Source Maps (OSM, on which the book’s mini maps are based) can be free, but in my experience you can’t beat centuries of refined cartographic know-how.

And with mapping apps like IGN (or indeed Google) you can download an area of map for offline use when there’s no 4G – quite likely if backcountry France is anything like the UK. All phones have GPS so W3W will still work, or at least show points, if not background map tiles. On long river days in France I’ve often lost track of where the heck I was and how far salvation might be. A handheld GPS device (eg: Garmin) or a mobile app running offline maps is the answer to nav connectivity.

The Routes

About three-quarters of the 40 routes (full list right) are there-and-back or loop paddles in the 5-12km range and can be just a couple of hours on the water. On a lake a loop makes sense, but where possible, I’d rather paddle a river or a coast one-way and bus or even walk back. The outdoorsy author has done big hikes herself; it’s a shame she missed out on ways to combine both for those with portable inflatables like hers, but there-and-back day trips are what most people do.

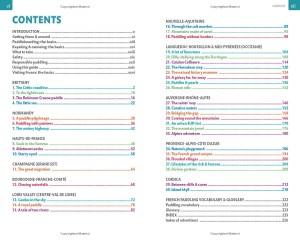

About 15 routes are inshore sea paddles divided equally between Atlantic and Mediterranean. Another 15 are rivers (9 are one-way), and 7 are lakes, with a bit of overlap all round (estuaries, reservoirs, canals, weir-ed urban rivers, and so on). As you can see in the Contents, each route gets a descriptive heading which is a nice touch.

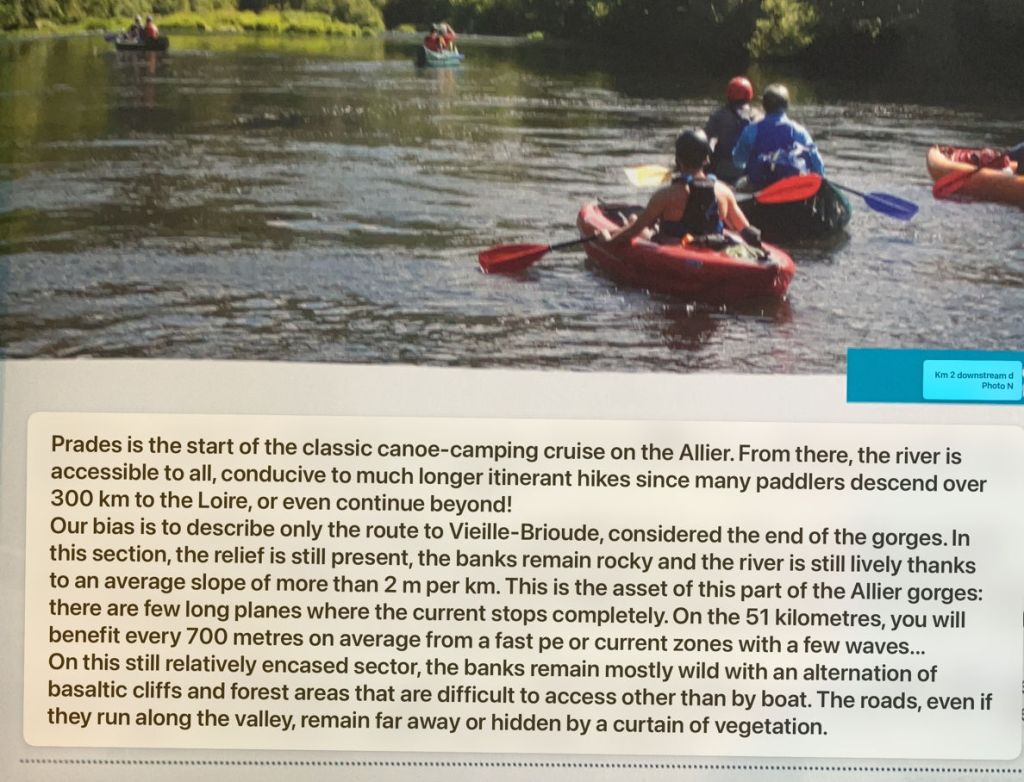

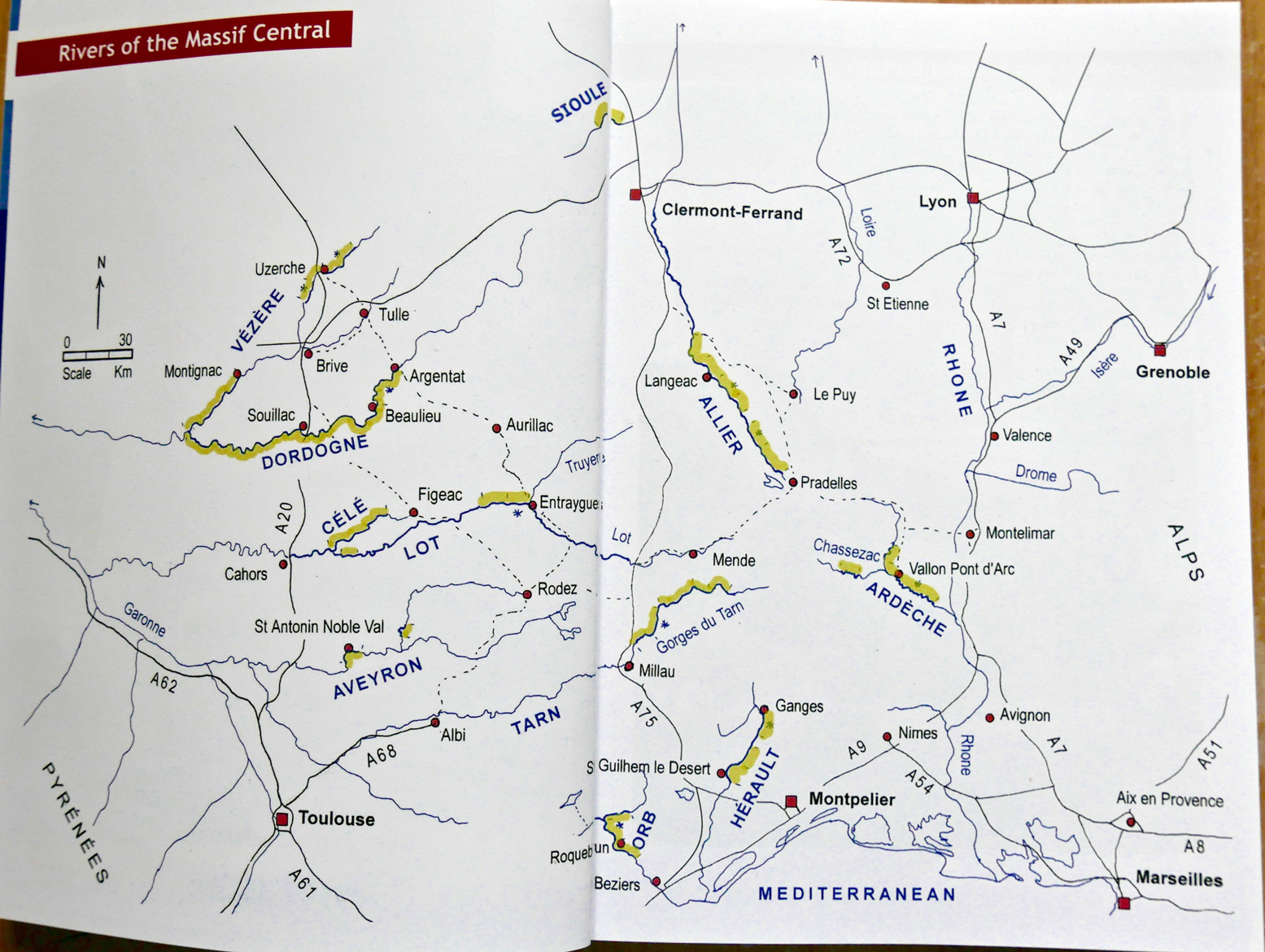

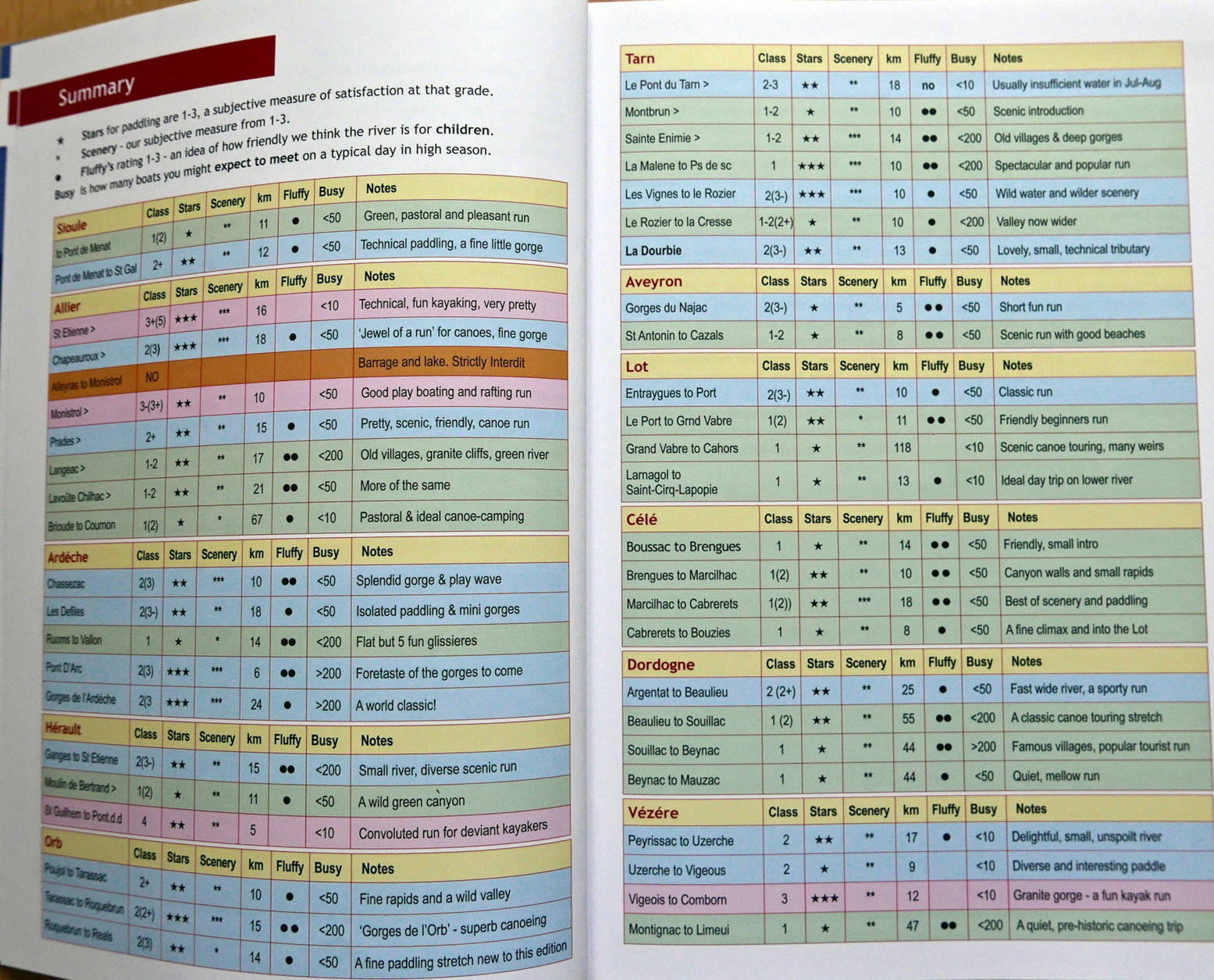

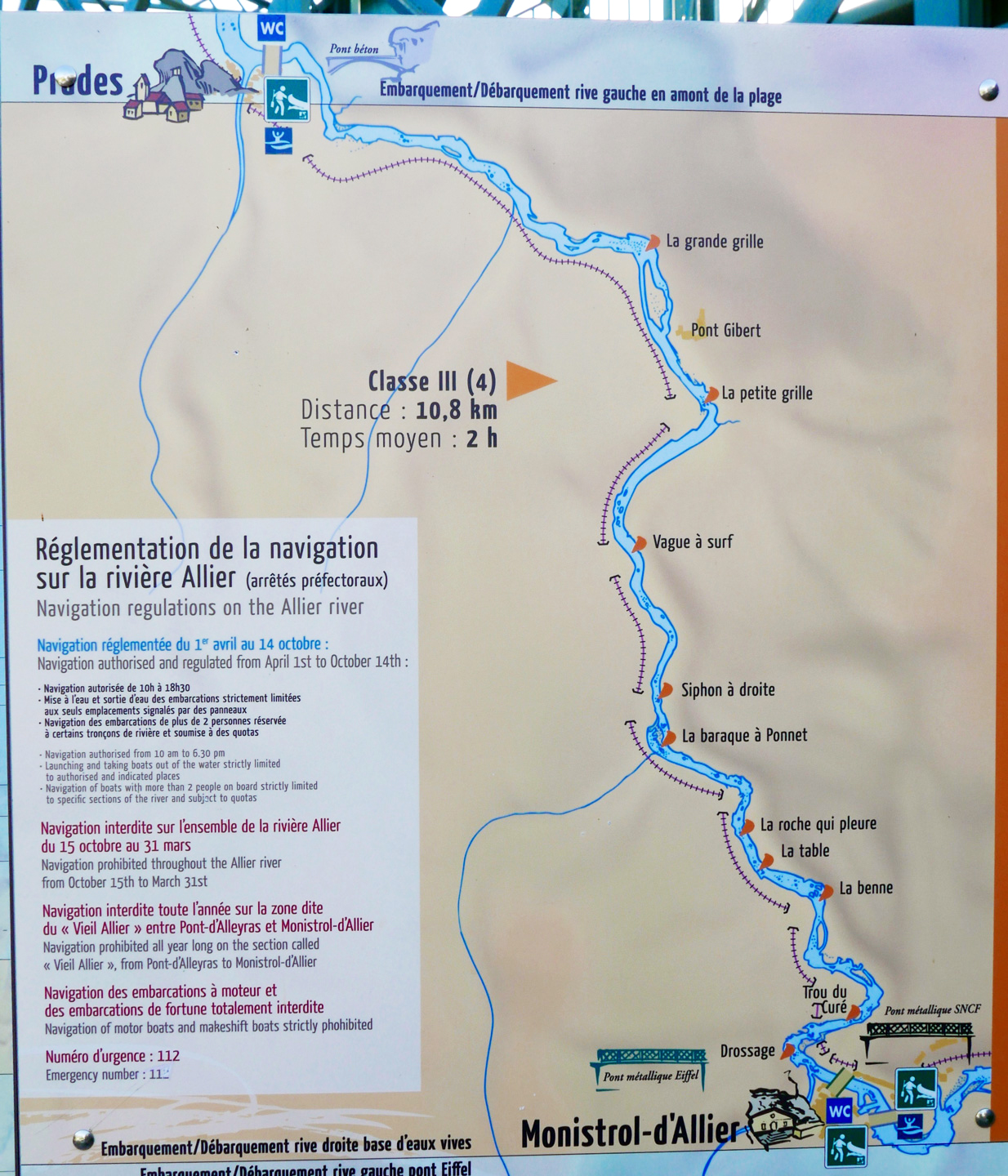

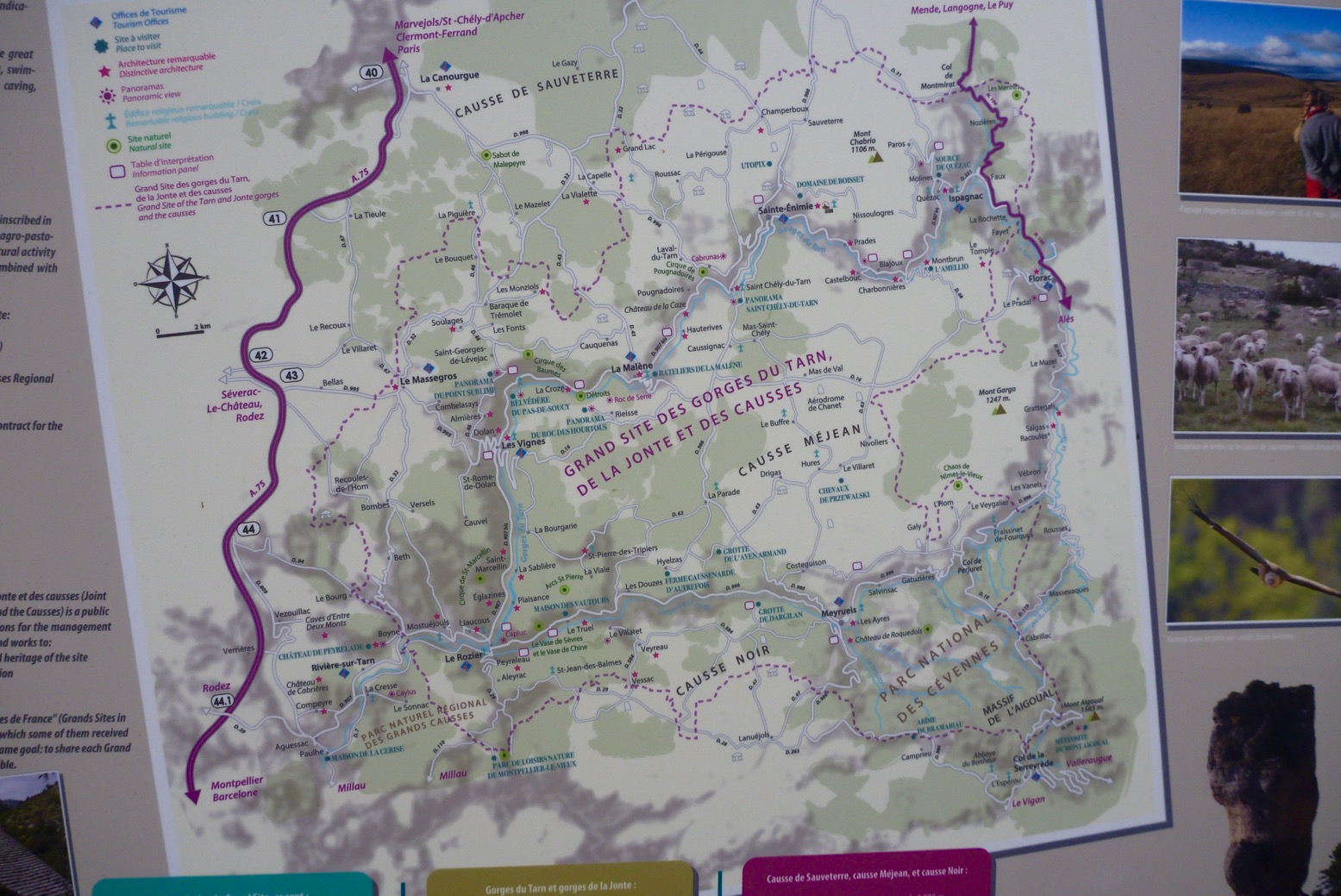

Each route also gets difficulty ratings from 1-5 for SUPs, and another for kayak/canoes. As you’d expect, most are easier or safer in a kayak, but all will be dependant on experience, river levels or coastal winds. The few one-ways are all great rivers in the Massif, like the Tarn (only 10km), Allier (11.5km) and the famous Ardeche – at a full 32km by far the book’s longest. The shortest is less than 2km, or 3km through the Il de Ré’s salt marshes (Route 16) – the sort of paddling locale probably better appreciated standing on a board.

Routes I know

Like any know-all reader I ‘tested’ the four routes I’ve paddled through at least once to see how they compared with my recollections. I read a few other interesting ones too, then skimmed the rest.

Route 20 on the Dordogne is a swift one-wayer of 11km passing several chateaux and ending with an easy bus trip back to the start. That’s what we want. I like the way some historical context is added into the narrative; as in the UK, it can be centuries deep in France. As it is you’ll be less than two hours on the water so best to string it out exploring some of the riverside villages.

The Dordogne was my very first French paddle in 2005: a full 101-km of meanders and piffling riffles between Bretenoux and Tremolat. By the end I found it all a bit easy, but still fondly recall a deliciously expensive lunch at Milandes (above left), then randomly crawling off the river exhausted that evening, dumping the Gumotex Sunny in some undergrowth and squelching onto the grounds of what I now see was the luxury Manoir de Bellerive hotel. I was too tired to talk myself out of it.

We’ve done the full 86-km of the Tarn (Route 23) from Florac to Millau at least 2.3 times using trains, planes, buses, taxis, IKs and packrafts, and the 11-km of this route took us just 90 dawdling minutes. As the book suggests, your eyes will be out on stalks, but it’s a shame to come all this way for half a morning in the amazing Tarn Gorge.

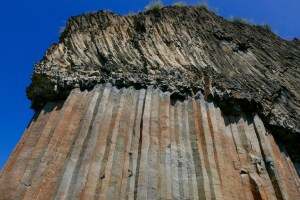

We also put in at La Malene one time, but following the easy 10-minute portage around Pas the Soucy (left; we clocked 9km), we did another 12km via Les Vignes to Le Rozier, capping a satisfying and spectacular day on the Tarn.

The book advises to ‘disembark’ before Pas de Soucy a ‘gnarly waterfall… which shouldn’t be attempted … unless you’re seriously professional‘. Shooting waterfalls can be a survivable stunt, but Soucy is a far more deadly rockfall with several syphons – another white water paddlers’ nightmare. It’s a serious mistake to make as photos show the author on her SUP so she was right there.

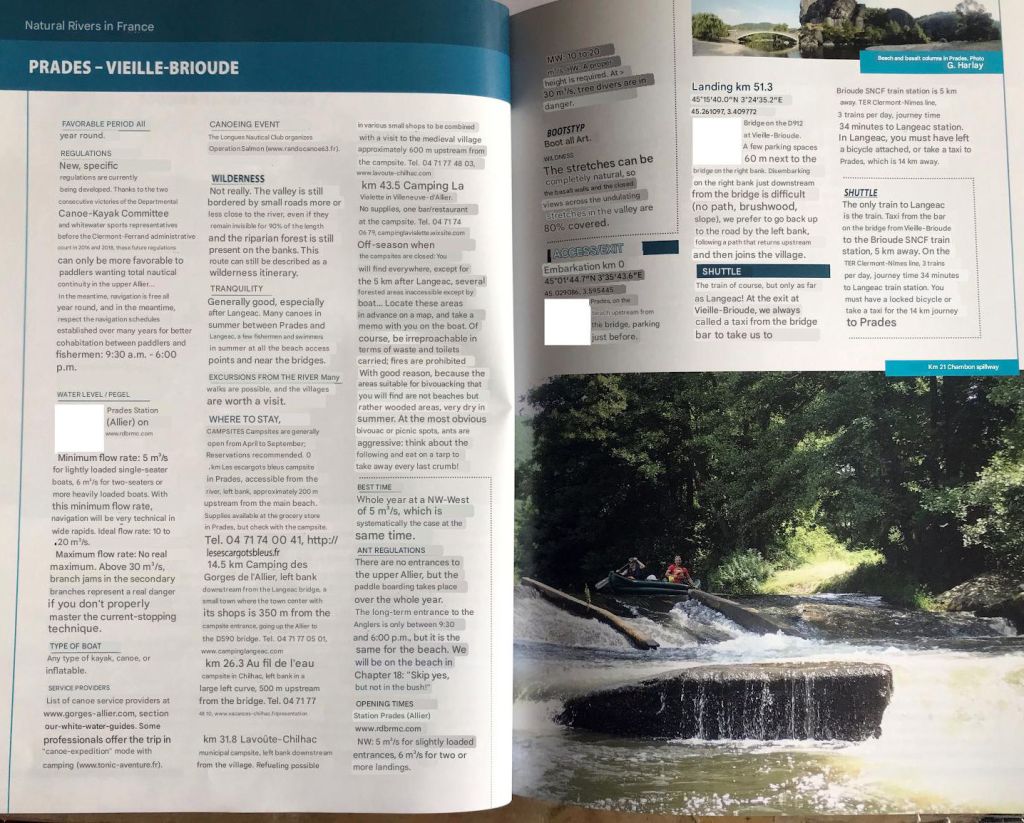

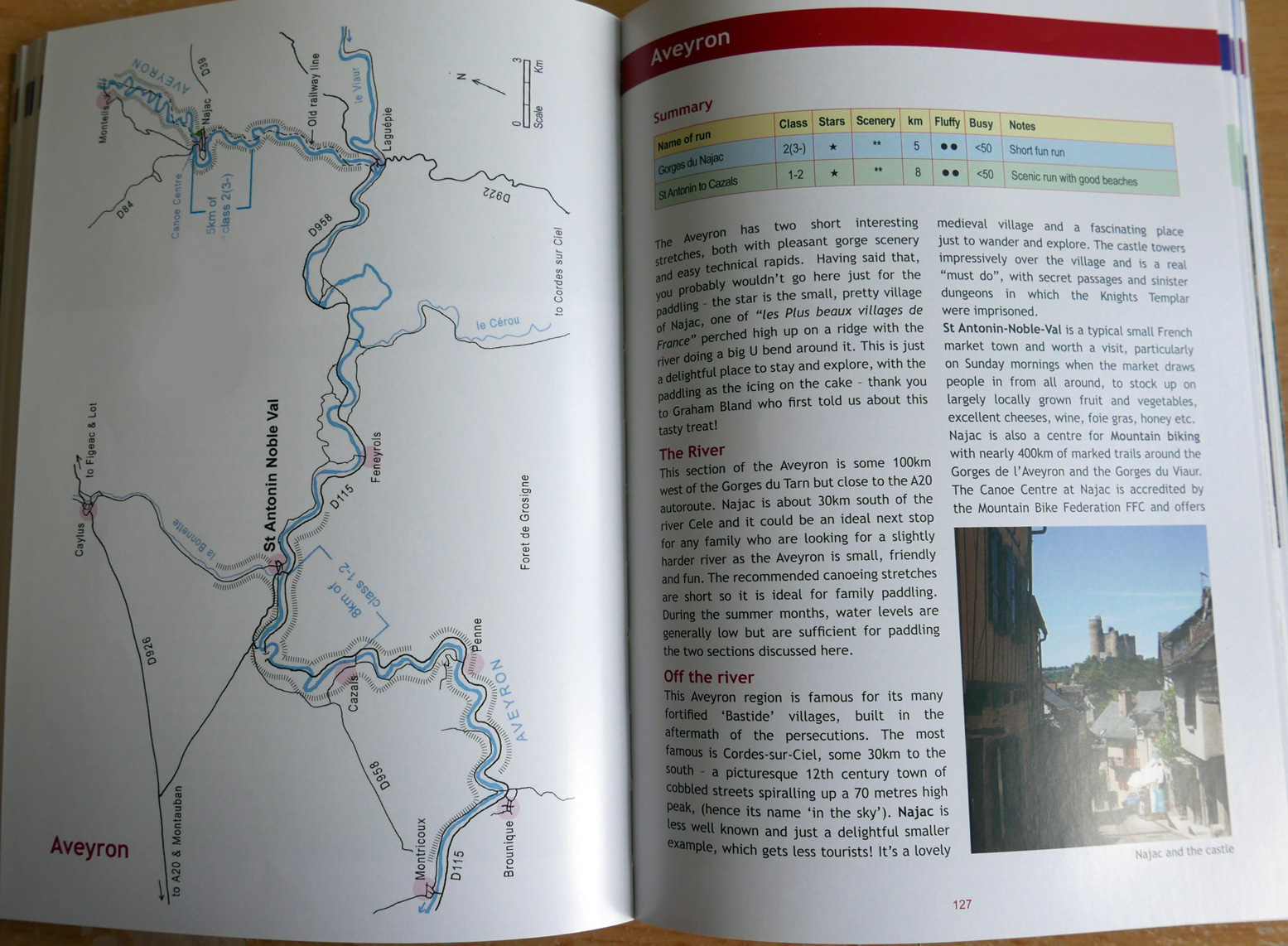

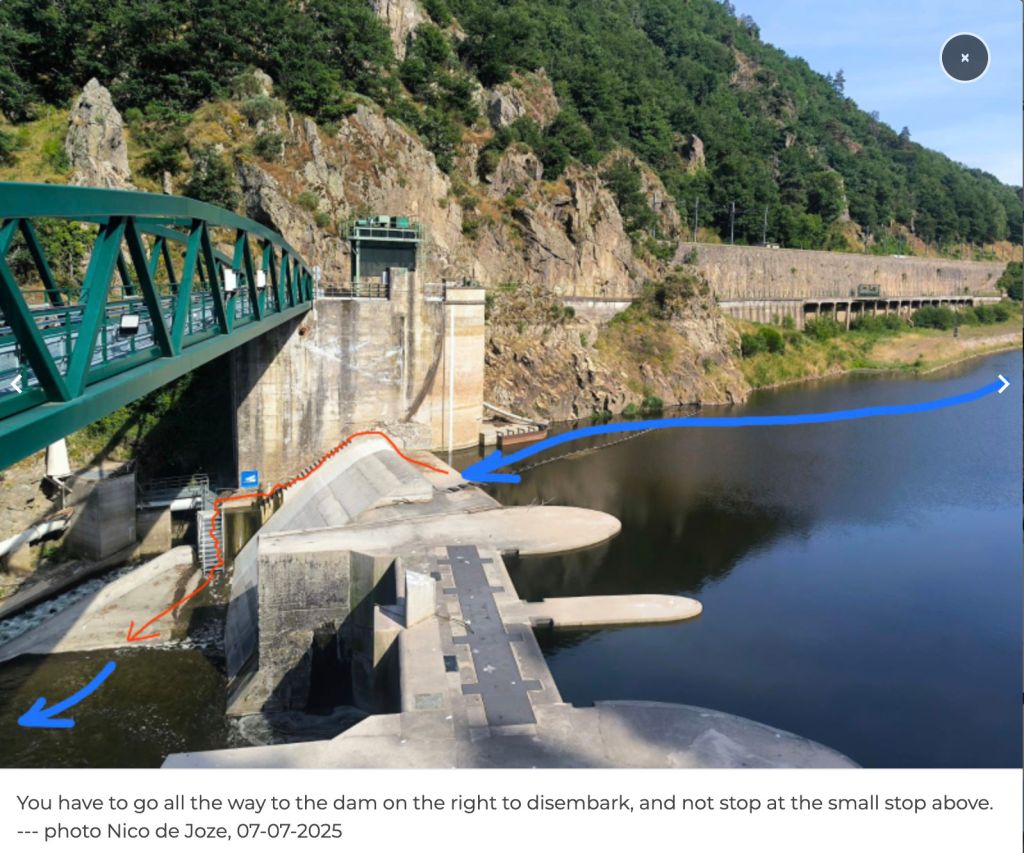

On one of my favourites, the Allier (Route 27; 11km), you wonder why choose the hard to reach put-in at le Pradel, when Prades hamlet with shops, toilets, parking and a popular put-in beach is just a mile up the road? Perhaps partly because the rental outfit dropped the author here?

Many of the book’s one-way river paddles seem predicated on the put-ins and itineraries of local kayak tour/rental operators (who each get a usually sole mention), rather than what would suit independent paddlers in their own boats and other means of getting around. With or without vehicles (or unwilling to use taxis), such paddlers could do a lot worse on the Allier than Langeac to Brioude, 38km. The two towns are just four stops (30 mins) apart on the Cevenol train line which followed all the way up the Allier gorges is a day out in itself.

Route 29 is the Ardeche, the longest in the book by far at 32km, of which the author says: ‘If you do one route in this book, make it [the Ardeche]’. This proves Anna Richards gets the appeal of doing a full day, one-way paddle, instead of two-hour there-and-backs which can be done back home on any summer’s evening. ‘It will leave you speechless…’ she continues. There’s certainly nothing like it (or the nearby Tarn) in the UK which is why in high summer you might get crushed in a white-water logjam of upturned rentals.

For a long time I was put off the Ardeche, misinterpreting Rivers Publishing’s description, and for Paddling France the author recommends using an SoT over her paddleboard. A lot of the time long, damage-prone fins are given as the reason not to ‘board similar rivers, but surely shorter or bendy fins are available? I’d assume the bigger risk is losing balance and whacking your head or breaking your collarbone in shallow rapids. Or the fact that when sat down for safety, your average SUP steers like a sea kayak with half a paddle.

In a bombproof packraft the Ardeche was plain good fun, made all the more memorable by the hoards of flailing revellers I’d normally seek to avoid. We came down over a week from Les Vans via the Chassezac tributary, covering about 70km.

Many famous spots like the fabulously chaotic Charlemange rapids just before the arch (above and above left), and the Dent Noire rock (where emergency services stand by on busy days) go oddly unmentioned.

Of the rest, everyone will find some great discoveries in Paddling France. Who’d know to try out the allotment-fringed canals of the hortillonnages off the Somme below Amiens’ gothic cathedral (below; Route 9). Other urban paddles also offer a novel viewpoint on a city which SUP-ing makes easier. Then there’s amazing Etretat on the Normandy coast which is probably geologically contiguous with Dorset’s Studland stacks over a hundred miles away. You’d hope that the rest of the sea paddles on this wild coast have been selected for their accessibility – probably so as rental outfitters will mean they’re a recognised thing. The sight of the book’s sole IK on p5 (Route 1, Corzon peninsula) was heartening, and the glittering granite sand spits of Glénan islands look like a mini Scilly Isles, though you’d think calm days here are infrequent.

There are loads of tempting locales, and of course the book’s many brief itineraries can easily be extended if you ask around or consult other guides.

For her first guidebook Anna Richards has done a great job putting it all together. While it’s not that hard to find brilliant paddles in France, each route offers a locale with a proven appeal and rentals on site. Paddling France is easily worth 20 quid to have this information and inspiration in your hand to browse.

A lot of my reservations are picky, but a printed guidebook from an established travel publisher carries an authority than online braying cannot match, and with it comes responsibility. Much more so for paddling, I believe, than walking or cycling guides, for example. After a quick flip through, Bradt’s Paddling Britain seems to have achieved this. As detailed above, a tiny amount of work would get Paddling France close to the calibre of that book and the other paddle guides mentioned. If the author didn’t have the paddling experience before setting out to write this guide, you’d think she had it by the time the book was finished.

When I first got into river paddling I thought ‘How do you know that round the corner you won’t get swept into some deadly rapids or sluice with no way of easily getting ashore?’ For this reason, river guides are different other outdoor activities. You can’t always get off the ride quickly or at all. Your typical happy-clappy SUPy Puppy (and budget IK user, for that matter) buys a paddle craft online and hits the water, literally not knowing one side of a paddle blade from another (as the author also notes). Paddleboarding may be associated with the trendy Slow Travel movement, but on the water you can get in trouble fast, which is why it’s important to be across the risks and regs.

We all have to start somewhere but in my experience, despite months of hard work, all this can often be too much to catch first time round, and to a busy publisher it’s just another title in the production line. Bradt is not a specialist in nautical publishing but a quick pass by a paddle-savvy editor would have caught most of the clangers. With a bit of distance and feedback, very often a guidebook’s second edition is what an author endeavoured to write first time round. I look forward to reviewing that one too.