Sea kayaking on the Ningaloo? It’s here

Packrafting the Fitzroy River – this way please

Originally written in 2010

“Why doesn’t anyone paddle around Shark Bay, Jeff? It seems ideal for beginners like us.”

“Name puts them off I reckon. It’s famous for big tiger sharks. National Geographic did a doco there once.”

“Oh really?” I said. “I thought it was just a name…” and took a thoughtful sip from my coffee.

It was 2am in a roadhouse on the Coastal Highway north of Perth, Western Australia (WA). I’d flown in from London that evening with my boat-in-a-bag and together with Jeff’s girlfriend Sharon, we’d hit the road for the 1000-kilometre drive to Shark Bay.

Perth-based Jeff and Sharon were river paddlers and windsurfers and I’d done a couple of French rivers in my trusty Gumotex Sunny as well as some coastal days, but the three of us were new to sea kayak touring. All we wanted was a safe but inspiring introduction and despite the name, we were sure the shallow, sheltered waters of Shark Bay fitted the bill.

The Bay itself is really a stretch of the otherwise exposed WA coast on the Indian Ocean, and the Shark Bay area is protected by two thin peninsulas which protrude north for 200 kilometres, like elongated harbour walls. But at an average depth of only ten metres, Shark Bay is of little use to shipping and is best known for the daily dolphin visits at Monkey Mia beach. A regular tide of tourists flow in and out of the resort, but having made regular visits there myself as a guidebook writer, I’d long suspected there was more to this ‘Australian Baja’ than beachside photo opportunities with Flipper and the family.

Apart from anything else, Shark Bay is a UNESCO World Heritage site, at the time one of only a handful which fulfilled all four criteria, being an area of evolutionary significance; ongoing ecological processes; superlative natural phenomena and biological diversity. With such impressive credentials we were sure its less-visited corners would be ideal for a mid-winter’s exploration in kayaks.

Once I established with the local parks service that paddling in such an exalted environment was permitted (Australia is full of rules), I was surprised to find just one online account of a kayak tour of the Bay: a quick visit by Australian canoeing legend Terry Bolland. Compared to Bolland’s adventures in the croc-ridden inlets of WA’s northern coast where ten-metre tides run like rivers, his Shark Bay excursion read like Lance Armstrong pedalling down to the shops to buy some milk.

Jetlag meant I was conveniently wide awake for the overnight drive and as the sky coloured with the dawn, we crossed the 26th parallel and passed a sign welcoming us to the fabled ‘Nor’ West’. We rolled into Denham, halfway up the Peron Peninsula and Shark Bay’s only settlement, populated by a mixture of snowbirds living cheek-by-jowl in the caravan park, permanent retirees in pristine bungalows and some fishing and tourist operations. We parked outside the café and waited for it to open.

For once the plan was not too ambitious. Paddle north from Denham about 60 kilometres to the tip of the Peron Peninsula, round Cape Peron to the east side, then cover the same distance south to Monkey Mia Dolphin Resort, a trip that might take up to a week. We aimed to take advantage of the prevailing southwesterlies on the exposed west side of the Peron and deal with the same as headwinds on the more sheltered southbound leg.

There was no fresh water anywhere on our route, and even the townsfolk of Denham had to pay a premium for desalinated drinking water.

So after breakfast we followed a network of 4×4 tracks to the tip of Cape Peron, our halfway point, and buried a cache of water and snacks. It saved carrying very heavy loads and should take us about two days to paddle here.

Setting Off

With our cache stashed under the paprika-red cliffs of Cape Peron, we set off from Denham at dawn the following day. Jeff and Sharon had a Perception Eco tandem kayak the size and weight of a tanker.

The waters were soothingly calm and soon a reliable southwesterly saw Jeff hoist his Pacific Action sail on.

“Bye,” I said forlornly “see you later.”

These propitious conditions didn’t last long. Soon the wind swung to the northwest, obliging us to dig in for what was to be two-and-a-half days of relentless battling. I actually enjoyed getting my teeth into a headwind, buoyed up by sightings of the extraordinarily rich marine life that give Shark Bay its special UNESCO status.

J and S took pity on my kayak-shaped lilo and hooked me up for a tow to the first of many mostly unnamed capes by which we’d measure our progress across a marine chart.

Sharon had chalked up a checklist of ‘must sees’: turtles, sharks, rays, dolphins and dugongs (sea cows). By our first beach break a green turtle had already passed beneath her bows and later, as we towed our boats through the knee-deep shallows up to half a mile off shore to rest the arms, startled manta rays submerged on the sandy seabed took flight as if shot from a bow.

Our destination that first day was the intriguing Big Lagoon which probed the peninsula’s flank like a tidal glove and promised a sheltered camp site. Twenty kilometres out to sea, Dirk Hartog Island broke the horizon: Australia’s westernmost point. The Dutch seafarer recorded the first European landing there in 1616, nailing an inscribed pewter plate to a pole. What he saw of the newfound Terra Australis was uninspiring: flat, arid and dense with scrub. It was another 150 years before Captain Cook mapped Australia’s less harsh east coast and brought about British colonisation.

A less historic lone pole marked the mouth of Big Lagoon, and as we rounded the entrance a mass of cormorants took flight, the air filling with the whiff of their oily wings. Though we’d snacked on some oysters during our afternoon wade, the day’s hard paddling had given us all an appetite so we pulled over among some mangroves for an overdue feed and a reappraisal.

It was already 4pm, and with the tide and the wind now against us we decided to leave the exploration of Big Lagoon for another day and scooted across the channel to the nearest sandy beach to make camp. We hauled out boats the last few hundred metres to the tide line.

Walking with Sharks

Though only ranging around a metre, the tides in Shark Bay seem to have a mind of their own. Some days there are two as normal, but the following day there might be only one-and-a-half, or even a single 13-hour high.

This had caused Jeff some consternation with the tables, but dawn brought the tide right to our feet and once loaded up, we glided out across the mirrored lagoon. It was to be only a momentary pleasure watching our boats speed silently over the seabed; out in the open the northwesterly was hunched up, fists drawn and waiting. Heads down, we worked our way up the coastline, stopping to investigate an old pearl divers’ camp. Western Australia’s famous pearl industry had begun in Shark Bay in the mid-1800s and the corrugated iron stumps of the shacks around us, now brittle with rust, dated from that period.

Tiny fishes skimming over the surface alerted us to the distinctive tail and dorsal fins chasing them. Soon metre-long sharks began darting between our boats, racing at us then veering off at the last second in a flurry of spray.

We assumed the bulky silhouettes of our trailing kayaks kept the young sharks from attacking, a theory that gained credibility when Sharon ended up running towards the beach, screaming as the sharklets circled her menacingly.

Presently the waters cleared and we hopped back into the boats, steering out into the wind around sandbanks as a long line of ochre-red cliffs long passed by. As they ended we hauled the boats ashore to set up another camp and, with daylight to spare, wandered off to explore the beach.

I found a washed-up conch the size of a watermelon while Sharon and Jeff came across a midden of oyster shells left either by 19th-century pearlers or maybe the Yamatji Aboriginal people who’d occupied the Bay prior to colonisation.

To Cape Peron

Up with the sun again, but there was no calm put-in this morning. It would be another tough haul to reach Cape Peron and our mouth-watering cache. By 9am Jeff estimated it was blowing at 20 knots.

“What’s that in English!?” I yelled, although the answer was immaterial.

“About 30 clicks!”

Was it possible to paddle against 30kph winds? My gumboat flexed with the swell as the sea surged over the sides. Now, without the protection of Dirk Hartog Island, the unfettered Indian Ocean swells were crashing against the shore. Still, every vicious headwind had has a silver lining and as we hacked at the water, a pair of dolphins popped up to say hello. Less than 48 hours into our sea safari and only the elusive dugongs remained on Sharon’s checklist.

The seas were getting as big as I’d ever experienced, but I figured as long as the Eco did not disappear behind the swell it wasn’t that bad. I still find the idea of sea kayaking intimidating, but two days of hard paddling had toned me up and I felt confident I could face the day’s toil. Partly this was because my Sunny had the reassuring stability of a raft, even if that included comparable agility and speed! It was something I appreciated when, after breaching a gnarly reef to grab another snack on the south end of Broadhurst Bight, we set off to cross the bay to the northern edge.

That turned into a punishing marathon with the confused seas barging at us from all sides. Tying on to Jeff’s stern I’d worked the bilge pump regularly while the distant shore inched steadily by. All around the once-comforting seabed was now an unfathomable inky blue abyss.

Two hours later we staggered onto the sandy headland, having covered just five kilometres. Our morning’s efforts had put us just a couple of clicks from the tip of Cape Peron for a snack and after another forty minute burst, with my boat swilling again with seawater, we landed on the Cape’s sandy beach and retrieved our cache.

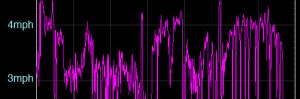

Stuffing our faces with jellies, sausage and now with plenty of water, we were keen to round the Cape because at last the wind would out of our face! We pushed out and once rafted up, Jeff hoisted his sail which filled instantly with a satisfying SLAP! Soon we were skimming along at two or three times our paddling speeds, water lapping over our bows, heading southeast into Herauld Bight.

Sailing with Dugongs

We were sitting back, our paddles over our knees and enjoying chatting without yelling when Sharon exclaimed

“Dugongs!!”

Several huge, dun-coloured profiles emerged against the dark seagrass bank on which they’d been feeding, and before long we were right among a herd of twenty sea cows, caught unawares by our stealthy windborne raft. At times our bows nearly ran over them, the water ahead exploding as their powerful tail flukes blasted them out of range.

By dusk our unexpected run downwind had doubled our day’s mileage. Once ashore I foraged for firewood while Sharon and Jeff got cooking. As we wolfed down our food, wafts of a gorgeous aroma drifted over from the fire. Intrigued, I walked over and realised one especially large chunk or timber was precious sandalwood.

A century ago WA had got rich quick supplying this raw material for incense to nearby Asia. Now the last reserves in WA were said to be in Shark Bay. We pulled the log off, finished off the meal and with the wind still blasting down the bight, retreated to our tents.

Across Hopeless Reach

By the time I’d dried out my tent after it blew into the sea, the tide had come in to meet us again and under sail we windsurfed round into Hopeless Reach.

Here, prophetically, the wind dropped and it was back to good old-fashioned paddling, albeit on much calmer seas. By mid-afternoon we could see Cape Rose a few kilometres from Monkey Mia resort. We didn’t want it to end yet and so strung out the day with fruitless fishing and exploring the scrubby cliff tops on foot.

As we approached Monkey Mia next morning, bottle-nosed dolphins cruised past, soon followed by a tourist catamaran and all the commotion of the resort.

We beached the boats one last time and while Jeff hitched back to Denham to get the van another ranger-led dolphin visitation ensued before a line of excited tourists.

Sure it’s fun seeing a dolphin close up, but the three of us couldn’t help feeling rather smug about our thrilling encounters out in the Bay. The tourists were standing ankle deep with half-tame dolphins, but we’d worn the paint off our paddle shafts, sailed with sea cows and walked with sharks!

See also: Packrafting in northwest Australia