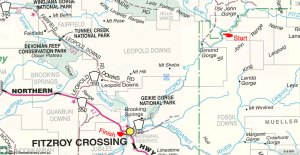

Fitzroy 1 ••• Fitzroy 3 • Fitzroy 4 • Fitzroy 5

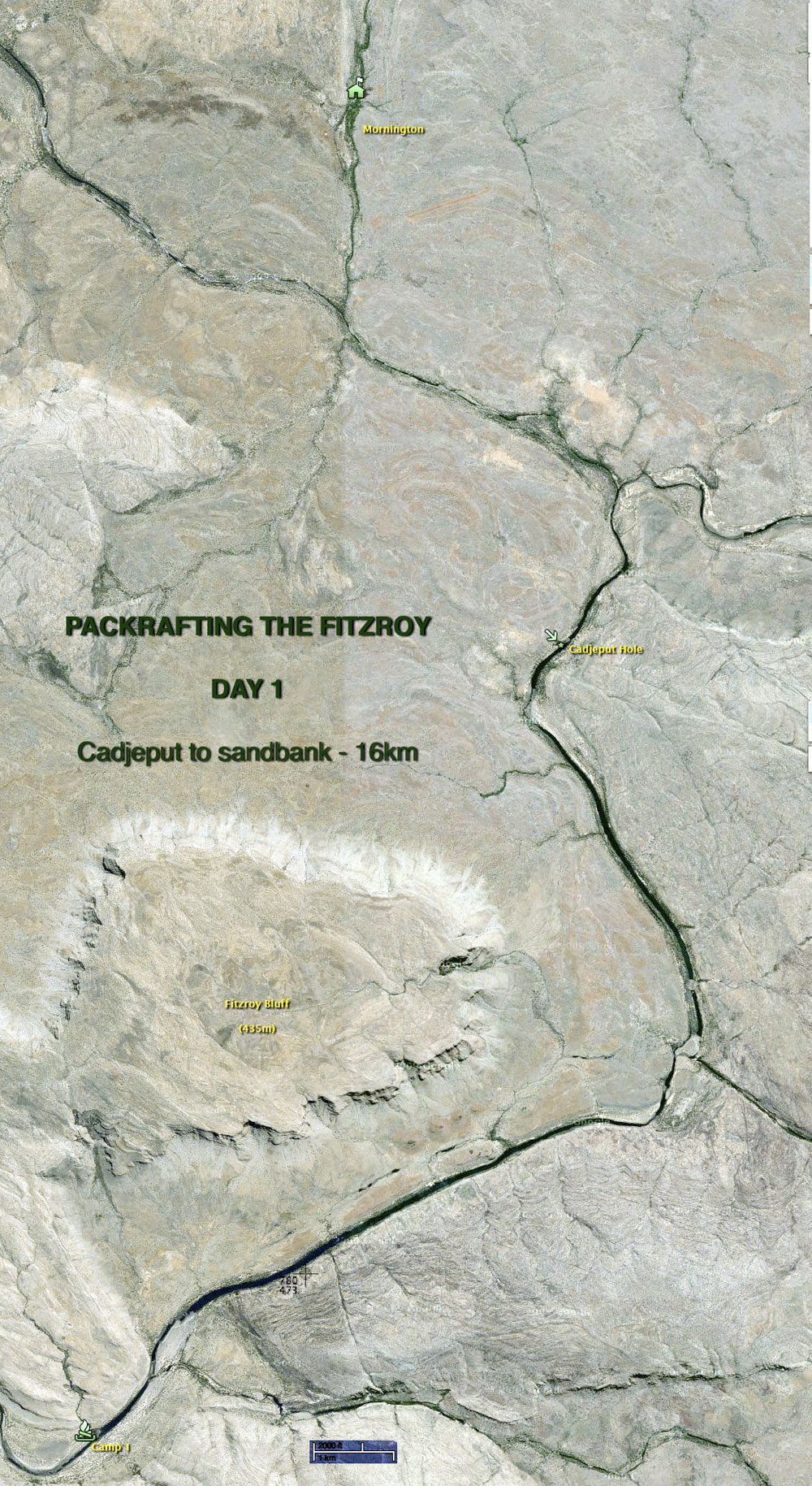

The video above covers Day 1 (previous post) and Day 2 which is this post.

By 5am the sun had risen somewhere behind the ranges and it was light enough to get stuck into our first full day on the river. I’d slept well enough on the unrolled tent under a thin blanket and all my clothes. Some time around 3.35am a hot, phantom wind had blown through our sandbar camp from the northwest. I’ve experienced these lost night winds elsewhere in the desert and always wondered where they come from and where they went.

Like us, in the cool of the morning both boats were a little flaccid after yesterday’s exertions, but Jeff was relieved to find his Bestway was still holding good air. Even then, after a brief paddle he decided to walk the remaining five kilometres to Dimond Gorge. Me, I was pleased to stay on the water, even if it occasionally meant skating across slime-covered rocks when dragging the boat through shallow rapids (left). Right along the length of Fitzroy, another six inches water and just about all rapids could have been run in our boats, but I don’t suppose it works like that.

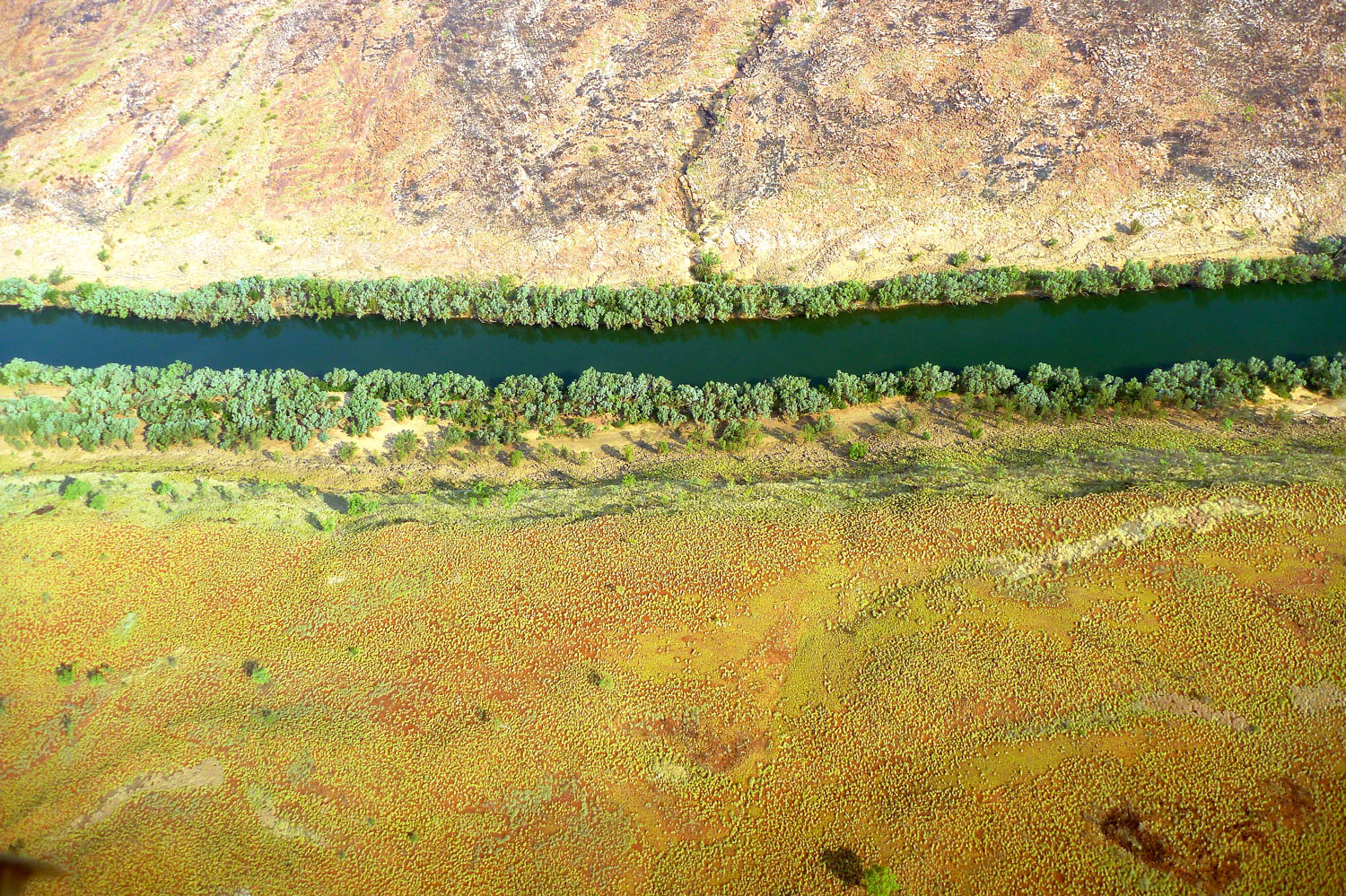

Jeff was now out of sight somewhere in the woods and soon enough the flow got shoved off the main channel by a blockage to burrow into the fringe canopy of trees where birds twittered and water monitors glared. This benign riverine underworld was a habitat I’d not anticipated, but was one of the most pleasant environments we found on the Fitzroy. Like a Damascene souk, shaded from the heat and glare of direct sunlight, you felt protected, cool and soothed while cockatoos squawked, rainbow bee eaters darted ahead and lanky-necked egrets stalked the pools. While pushing, pulling or paddling the boat through these cool causeways, I was reminded of that cool picture of Ed Stafford hauling his heavily loaded Alpacka through the Amazonian swamp.

A couple of hours later I was back out in the open and squeezed the Yak between two rocks to slip into the top end of Dimond Gorge (above – downstream, and above, looking upstream). MWC left a few canoes here for day visitors and I pulled over alongside them, stripped off and dived in. Jeff turned up about 15 minutes later but it didn’t look like he’d enjoyed his bush walk and he simply dropped his dinghy in and set off along Dimond, knowing I’d catch him up soon enough. The headwind already funneling through Dimond from the plains didn’t improve his mood.

Presently the gorge turned left to break through the ridge and soon choked on the effort. It was here that the dam proposed over 50 years ago would have been sited, to match the Ord Irrigation Scheme near Kununurra in the East Kimberley. Although the idea gets revived once in a while, as things stand the Fitzroy is unlikely to get dammed here.

It was already 10am and with 8 or 9 clicks behind is, it was high time for ‘smoko’ as they call it in out here. As always, firewood was within arm’s reach and soon the billy was on the boil. We’d brought a gas stove in case high winds made real fires risky; on the way in from Broome we’d seen several roadside fires. Most were deliberate, late-season burn-offs, but we’d also heard some ultra-marathon racers had been trapped by a bushfire in a gorge on El Questro near Wyndham and had been very badly burned. If nothing else, it would be extremely bad form to start a bushfire on the station land we were about to cross, but we always lit up alongside the river where things remained damp and cool.

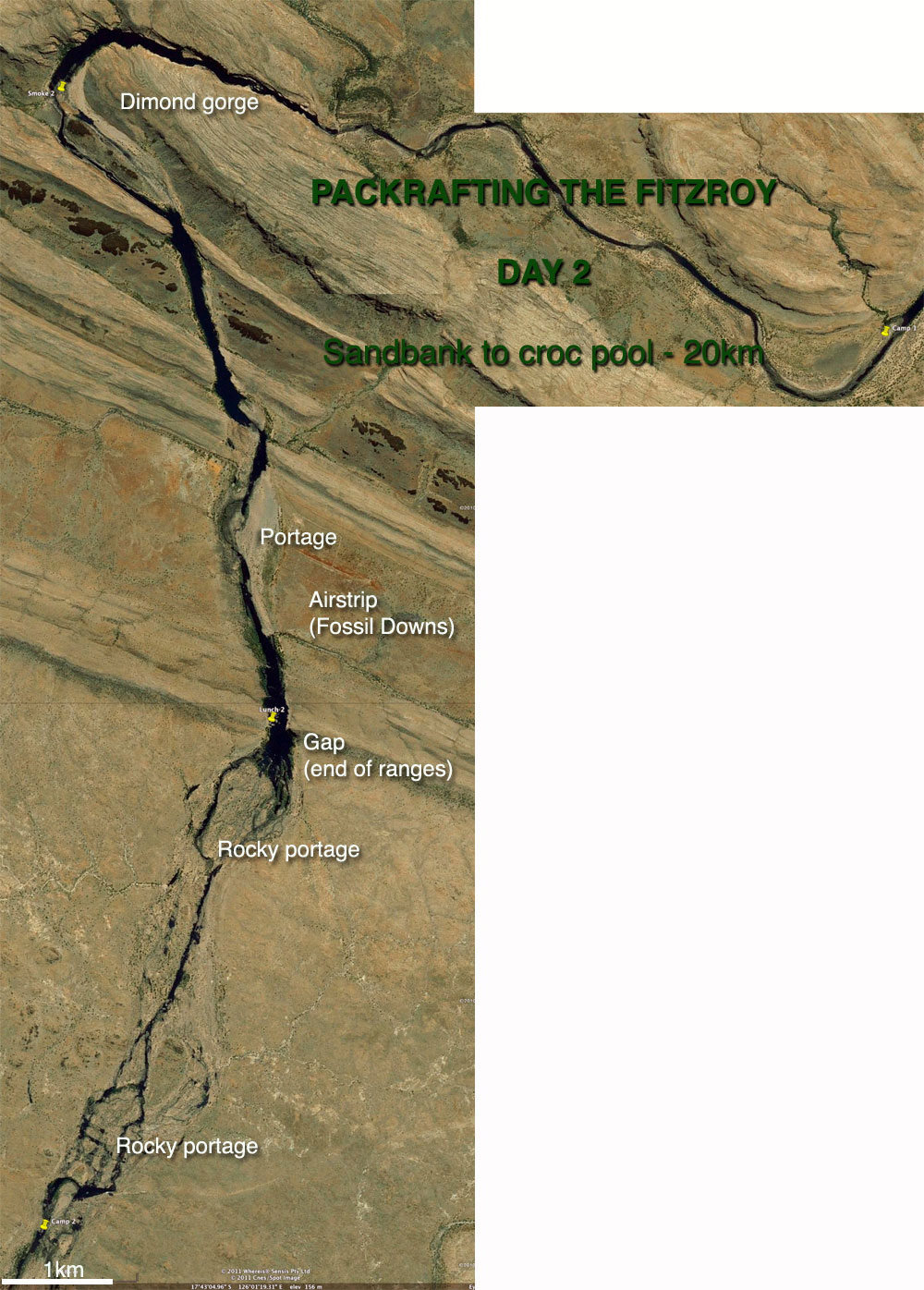

From this point it was about 6km to the next landmark – what we called the Gap, an opening in a low ridge like those found in the West Macs out of Alice, and which here marked the southernmost ridge of the King Leopolds. We’d seen it clearly on the flight in and with the headwinds persisting, Jeff decided to head off across the boulders while I paddled on for a couple of minutes, then portaged a very gnarly section. It looks like an easy 5-minute walk on the aerial picture but let me tell you with the head wind and my unstable pack, stepping between fridge-sized rocks with a boat under my arm was not a dance the Royal Ballet will be performing any time soon. At least the Brasher trail boots both Jeff and I had bought cheap in London were earning their keep here. Out of the shade and off the water, the heat bounced off the rocks, sapping the energy expended in carefully negotiating these rocky portages. I’d have to come up with a better system like Jeff, if these rough portages were to continue downstream.

I put back in as soon as I could, noticing we were now on granite, a little less smooth but also less coated in treacherous slime in the shallows, which made wading easier. Up ahead Jeff was putting in too and despite the headwinds held his own – clearly he was refining his Bestway paddling technique. As the conclusion of the video proves, Jeff was finding his pool toy to be more versatile than he’d initially hoped.

Another sweltering rocky portage led past some sort of sentry box and pipework river left, close to where an outlying airstrip lay on Fossil Downs land. It was a clear run from here against the wind to the Gap and the end of the ranges. We clambered onto a rock for a lunch of double cuppa soup and another hot drink. While the billy boiled Jeff threw out his handline; we’d been assured in Broome that the barramundi (northern Australia’s best know fish), would be huge so Jeff had bought a 30-pound line accordingly. But there was no fish for lunch on that or any other day while we were on the Fitzroy. They must be out there, but the only fish I ever saw where the size of my finger. It’s no wonder the crocs were so stunted.

Beyond the Gap we knew the river would change character as it weaved over the savannah for 60 kilometres towards Geikie Gorge. This would be the crux of the trip. Even though the flight had revealed several long and clear river channels, we’d also spotted masses of thick woodland with no clear path. We looked back at those aerial shots in our cameras to figure out the way ahead. Our goal that afternoon was to try and get west of 126°E and onto the next map sheet, something that in the end we only barely managed.

Soon after leaving the Gap we came to another big rock pile where the river braided out into nothing paddlable. In the mid-afternoon heat, clambering with all my junk was as much fun as roller skating on cobbles while balancing a sofa on your head, and using my packstaff for the first and last time was merely another encumbrance that threatened to impale me should I trip.

I desperately floated across the smallest pool, and when it came to the next big portage I simply left the boat and set off with the UDB pack. It took twice as long of course, but being able to see ahead and use my arms to balance, it felt safer. Perhaps it was hotter than we realised – getting on for 40° maybe? – but even before I turned back for my boat I was parched with thirst and croaked to Jeff, ‘Let’s camp at the end of the next pool’. Whatever the time was, we were beat!

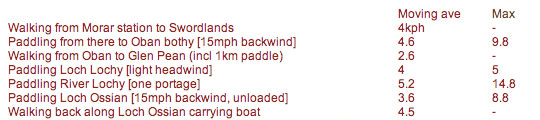

The GPS was no longer tracking as the batteries lasted less than a day, but it turned out we’d put in an 11+ hour day of only 20 kilometres, managing just 5km after lunch. At our poolside camp, I slung the gear into the bank, went for a swim and then drank and drank. Unless I’d some acclimatising to catch up on, this effort in portaging over the big rock bars was not sustainable; fatigue would eventually lead to a mistake and Jeff had already fallen a couple of times.

I needed to radically revise my portaging set up. My yellow Watershed ‘day bag’ was better out of the way inside the UDB which now sat in the boat not perched across the bow. That worked much better for wading and towing while I sat with feet plonked on either side in a suitably reclined paddling posture. Like this I could also access the UDB in the boat if needed, and forward visibility was better too while the Yak’s extended ‘fastback’ tail compensated for the rear-weighted trim. I’d also ditched my cumbersome water bag and now simply drank from the river. We’d brought my Katadyn and used it most evenings. Jeff stuck with it, but I found carrying a full day of water too heavy at the rate I drank it. I took care to drink from less skanky pools and flowing riffles and never got sick.

The water boiled and another two-course freeze-dried supper was wolfed down, along with several rounds of tea. Jeff was in bed by 6 – a personal best. It had been a tough first day and now we were heading into the meandering cattle lands we weren’t expecting it to get any easier as the river lost its definition. Jeff wasn’t convinced yet, but as I saw it, the key would be to keep track of the main channel and minimise arduous portaging at all costs by paddling or towing. Even then, we figured that as long as we didn’t get any more tired than we were tonight, and our once-daily bag meals continued to sustain us, we still had five full days of food for the remaining 100 kilometres and could trudge on at whatever daily distance we could manage until it finally ran out. By that time we’d surely be very close to Fitzroy Crossing.

It was a hot evening and out on the pool crocs, lizards or the elusive big fish were splashing about. I pottered around the camp for a while, putting off the unenviable moment when I had to squeeze into my too-short K-Mart tent to grab a mozzie-free night. I was still thirsty as I dozed off. Likely as not, tomorrow was going to be another tough one.