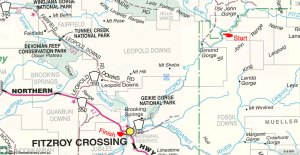

• Fitzroy 1 [intro] • Fitzroy 2 • Fitzroy 3 ••• Fitzroy 5

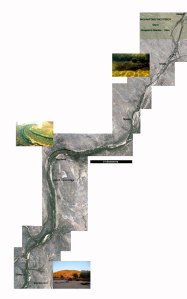

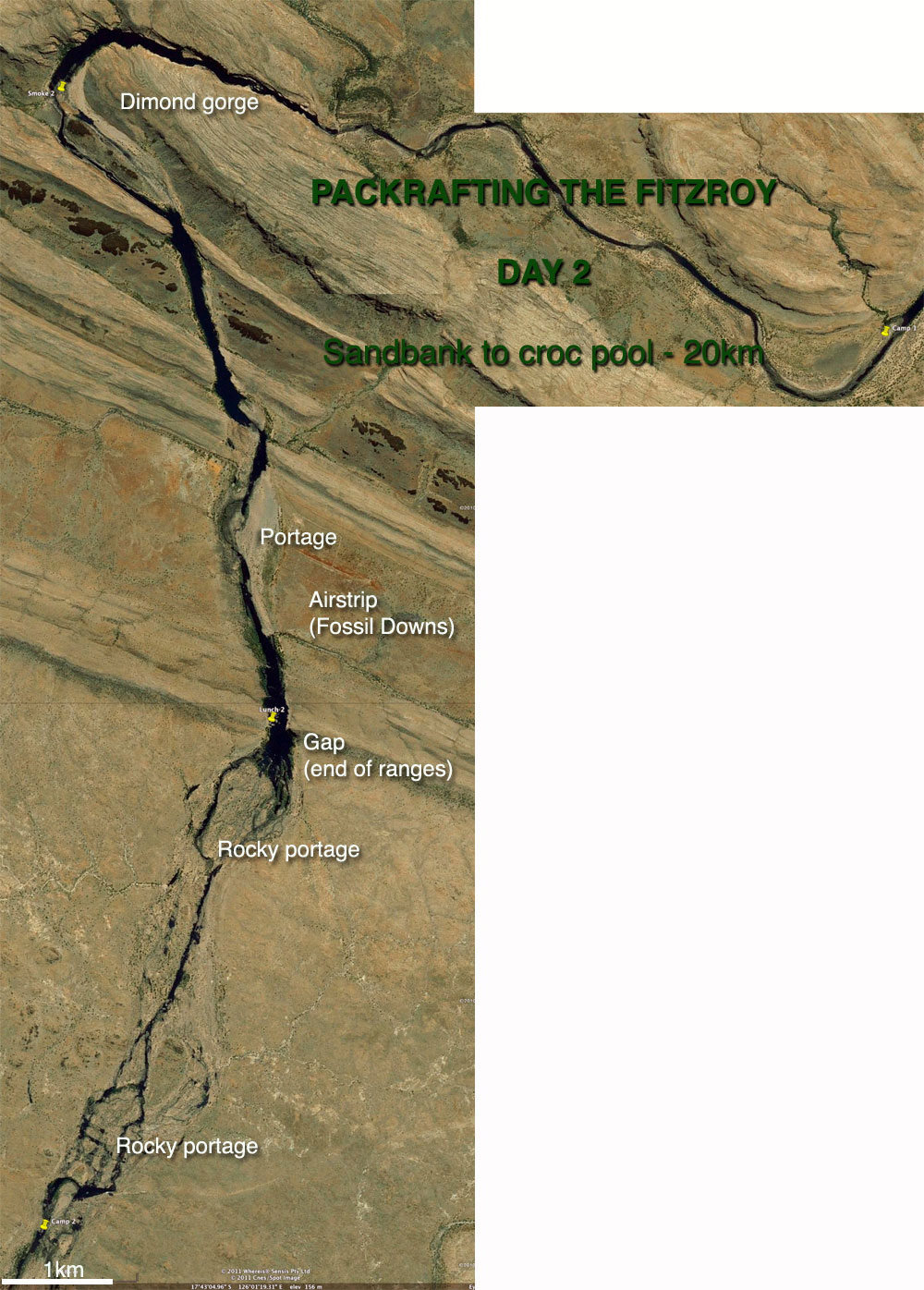

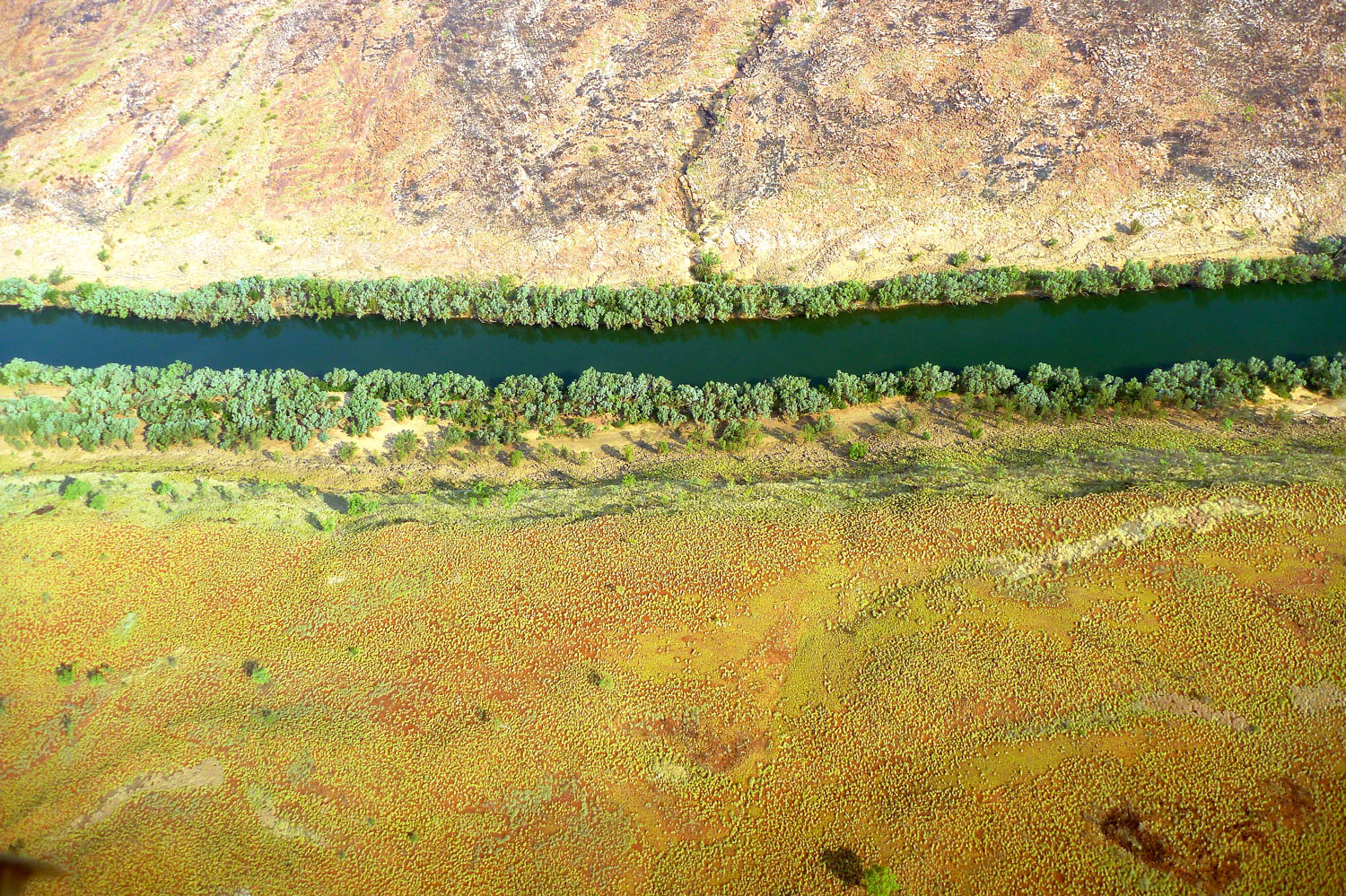

Soon after dawn we stood on a small hill overlooking our camp down on the sandbank (middle point map left or picture right). For the last couple of days we’d spent most of our time in the tree-lined river channels, seemingly separated from the outside world. Here was a chance to see what lay on the outside, beyond the river.

It was the same old gum-tree spotted Australia bush which covered most of the country, but up ahead a particularly thick mass of gums obscured the course of the Fitzroy. It did not bode well for an easy day.

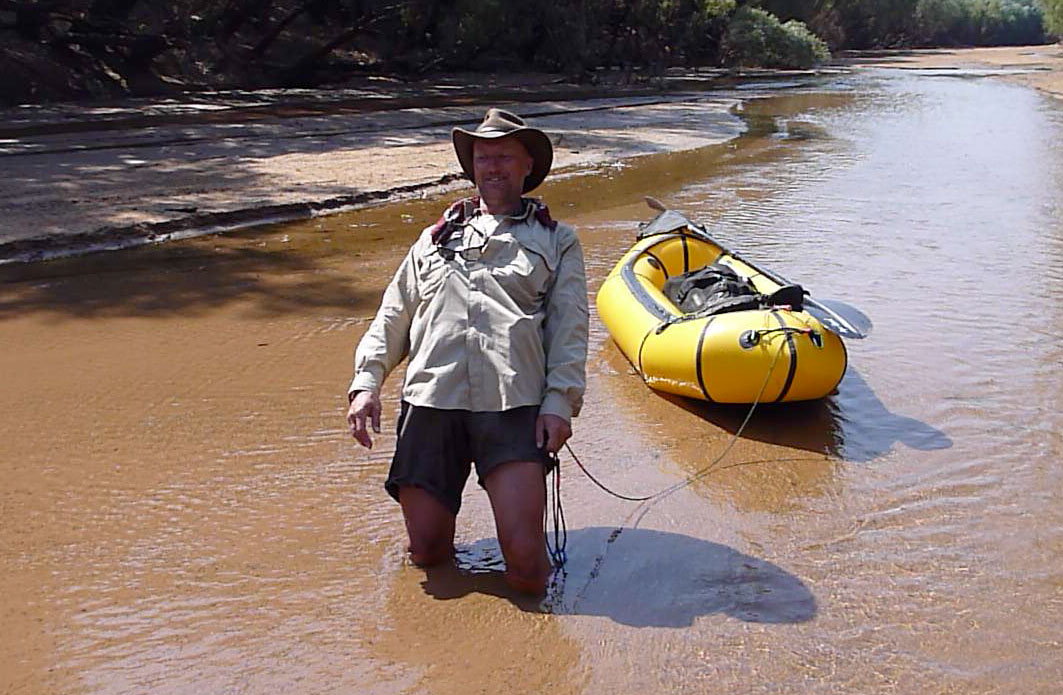

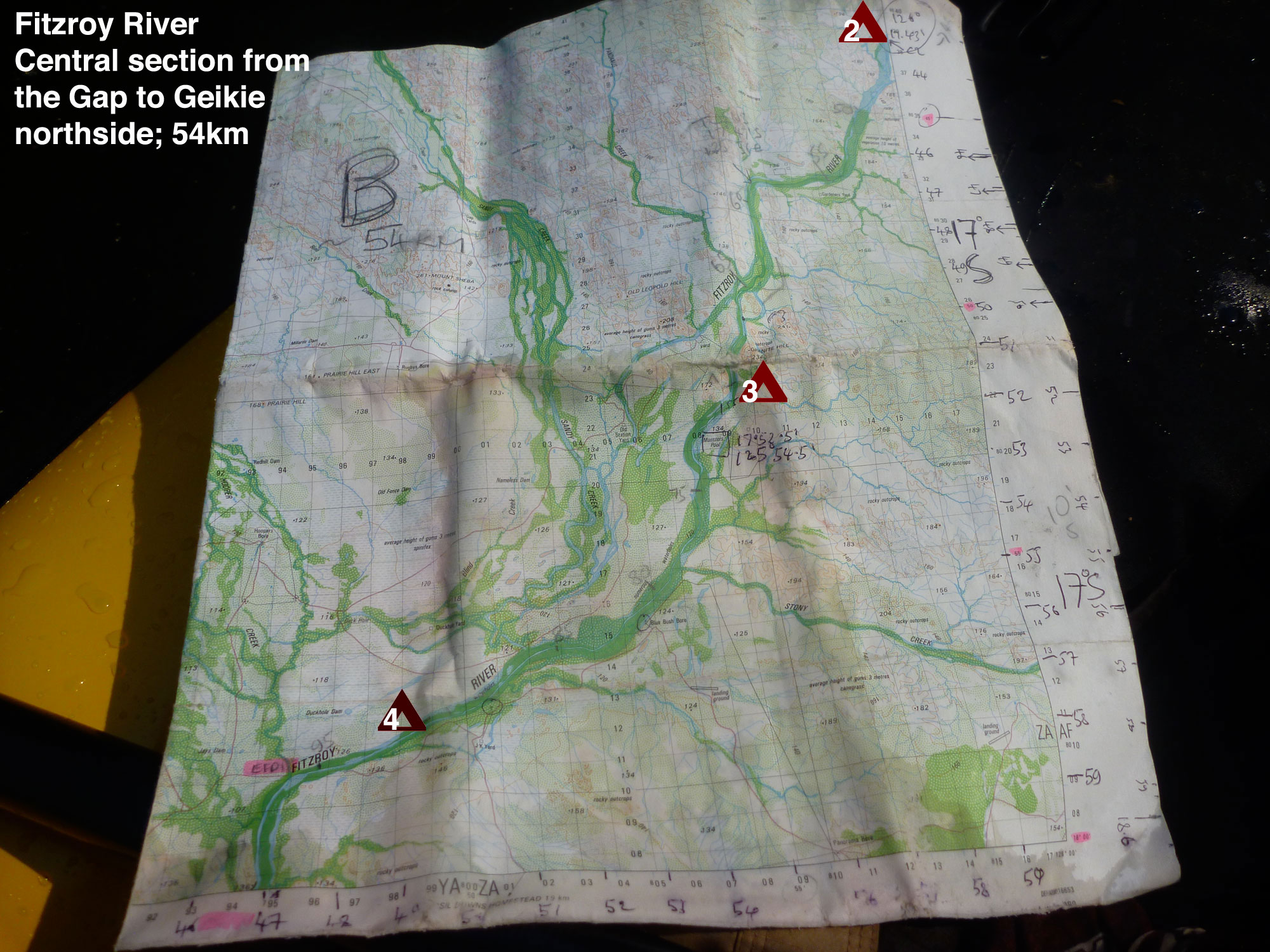

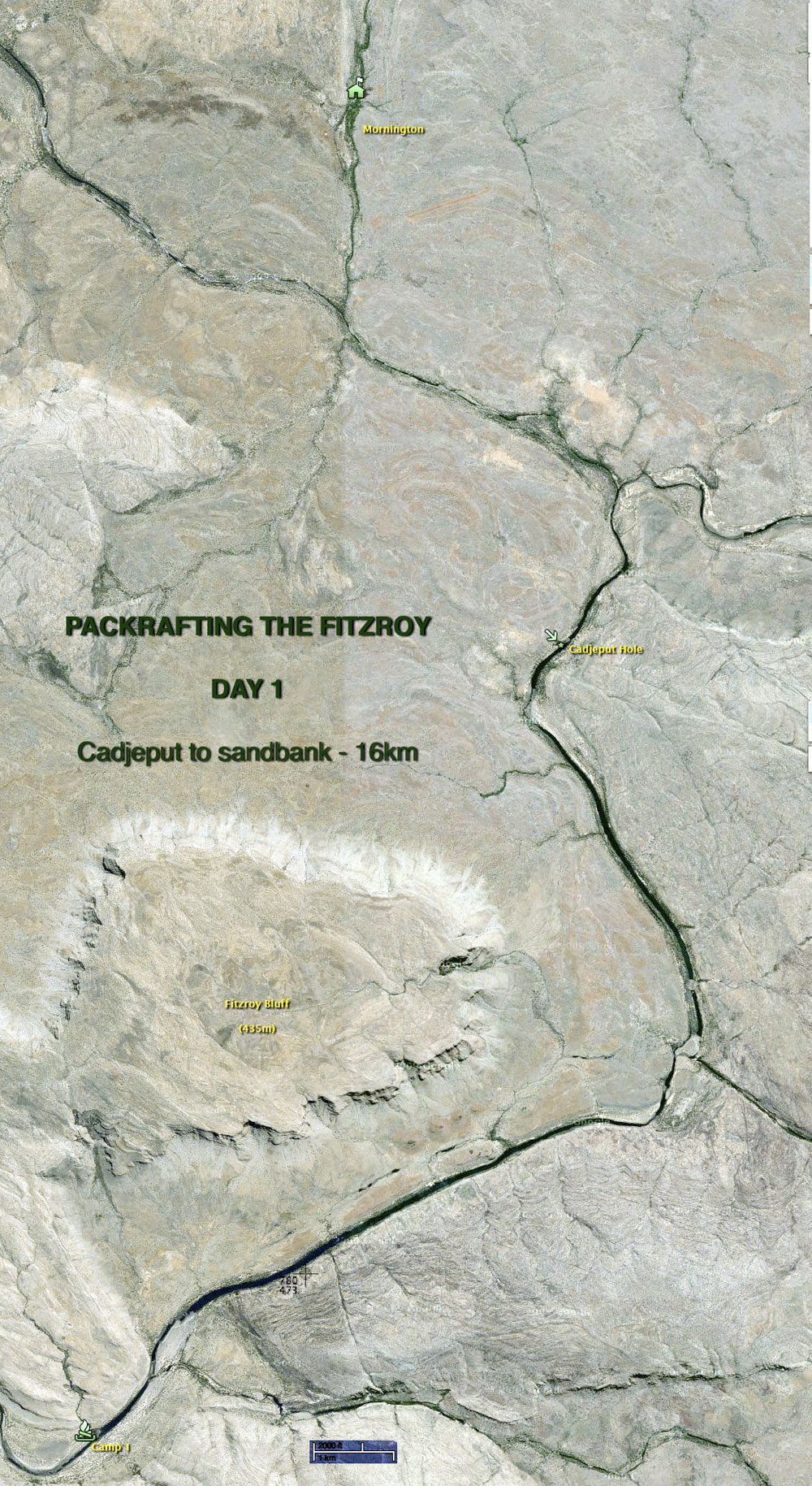

We set off a little later than usual, wading and paddling the shallows, but mostly walking with our boats. We passed Munsters Pool as marked on many maps, but it’s just another part of the river with a few cattle milling around. The flow braided and at one point I idly took a left stream while Jeff just ahead went right. I assumed they’d join up which they did, but not for 20 minutes or so by which time we’d lost touch with each other.

I’ll let the video above show how events unfolded, but I knew soon enough was my mistake for not following the one in the lead, even if that path might end up a dead-end. I’ve experienced this kind of unintentional separation several times in the desert on motorbikes: everyone knows best so you diverge round an obstacle as you think your way is better/easier and will soon join up anyway. Your path goes astray and round the other side you don’t meet up. The one ahead goes back looking for the one missing, the one behind thinks he’s way behind and rushes on ahead. Cue wasted time and frayed nerves.

On this occasion, once I stopped I was pretty sure Jeff was behind me, and sure enough, 40 minutes later he walked in from upriver after backtracking all the way looking for me, giving up and carrying on. Although we were both self-sufficient, from then we vowed to stick together – it was better for the film!

Soon after that we has smoko and tensions eased over a cup of tea. As we gathered wood I found a plastic bin lid which made a great over-sized frisbee and which Jeff later adapted into a seat to keep his butt out of the swill. Very soon that bin lid became handy as I came across a rich deposit of alluvial gold, sparkling in the shallows.

Jeff swilled the sediment around while I filmed, and very soon we had some colour. There certainly is gold in the Kimberley; WA’s wealth was founded on it in 1885 with the original gold rush at Halls Creek, the next town down the road from Fitzroy Crossing. And since pre-industrial times the low-energy method of surface mining has been to divert rivers into torrential ‘hushes’ which scoured away the topsoil to reveal precious mineral veins or ore. The 2011 flood on the Fitzroy had clearly exposed riches beyond our wildest dreams and I’d have to beat Jeff to death with the bin lid to get my hands on the treasure.

In the end we came to our senses and recalled that the lady’s assertion in opening line of Stairway to Heaven was most probably deluded.

The day proceeded to warm up with a series of short pools, very often preceded by tiring quicksands where the shallows became waterlogged. Elsewhere progress was slowed by log jams where the flow was forced into the trees lining the main channel which has become choked with sandy sediment dropped by the river after the flood. But along the entire route the Kimberley soundtrack of birdsong kept us company with its squawks, whistles, warbles and chirps. Today we saw a few blue-winged kookaburras and a couple of rainbow bee eaters along with the usual procession of egrets and cockatoos. In my guidebook-researching days I knew them all by heart and it was fun to jog my memory or be able to name what I saw.

Up ahead a welcome pool promised some steady progress – even Jeff was getting to like to the effortless paddling now. But very soon a strong reek of guano or urea choked the air, with the below water covered in a skanky film. A huge colony of bats where clinging to the river gums along the left bank, and with a shriek took to the wing as we slowly paddled by. Jeff explained the reason for the stench was that bats pee on themselves in an effort to keep cool.

At lunch I called Fossil Downs station to notify them a little late that we were on their land, (as they’d asked us to do). The old lady there seemed quite inspired by our mini adventure along the river which she’d never really seen but which watered most of their land. Still in the hands of the same family, Fossil Downs was established in 1885, making it the oldest cattle station in the west Kimberley. Although I’d never been there I’d always been in intrigued by tales of the comparatively palatial homestead and its marble flooring (or some such). In the Kimberley most station homesteads were functional affairs.

Just as yesterday, within a few steps of lunch Jeff got another flat, but fixed it in a jiffy by rolling the hole up with superglue and applying a duct tape bandage for good measure. We pressed into the afternoon, squeezing under trees or lifting the boats over or around fallen logs. At one point a rather mangy bull stood in our channel, sick and clearly agitated. Normally the cattle ran away; this one tried but got stuck in quicksand and didn’t have the strength to gallop up the steep bank. It turned round and came back to stand its ground. Filming all the way, Jeff got a little too close and the thing lowered its horns and ran at him. Eventually I crawled up the steep bank, and from point downstream but safely out of reach, coaxed the ailing steer upstream past Jeff and our boats by throwing sticks.

Since the bat colony the surface of the river had been pretty rank which didn’t add to the ambience. More bat colonies followed, and about 4.30 we came across another piled-up sandbank which filled the whole channel while the flow took off left into the side trees. A knot of fallen trees required lifting round to continue so we called it a day just as a helicopter flew overhead. With cow crap and bat shit all around, it wasn’t a great spot, but would have to do as we were just about finished for the day. In fact we’d done better than we thought: 10 hours to cover 26 clicks according to the map, and not far from the second Big Bend which led down to Geikie, possible ranger issues and the final big run on wide open channels.

That night Jeff prepared a brilliant garlic damper which we cooked on the coals. Real food – you just can’t beat it! It had been a hard day to end at a grubby camp, but we felt we’d finally broken the back of the Fitzroy.