We set out to paddle from Chichester Town Basin, down the old ship canal into the tidal Chichester Harbour at Birdham Lock. Lois and Austin in two do-it-all, drop-skeg Venture Flex 11s (left) Robin and Elliot in an old Gumo Twist 2 and a newer Nitrilon one, both of which fitted into carrier bags. Plus my Seawave lashed to a trolley.

Nearly two hundred years ago Turner depicted tall ships gliding serenely along the then new 4.5-mile canal (above). During the canal boom preceding the railways, it linked Roman-era Chichester with the huge natural inlet of Chichester Harbour and the adjacent naval fleet at Portsmouth. To the east was a canal to the Arun & Wey navigation (left) which was a short-lived inland link between London and Portsmouth commissioned at a time when Napoleonic fleets threatened the English Channel.

Our original plan had been no less Napoleonic in its grandeur: a 15-mile lap of Hayling Island, but today the tides and winds were all wrong for that, and even with Plan B we’d arrive at Birdham at low tide to face an undignified, sludgey put in.

On Google maps the canal looked clear, with maybe a quick carry around a lock or two. But just two miles from the basin, a thick mat of Sargasso frogweed clogged the channel at the B2201 Selsey Road bridge (below), reducing speeds to a crawl. Worse still, over the bridge this unallied carpet of errant biomass ran on like forever, and probably all the way to Birdham Lock.

Was it a high-summer frogweed bloom? The initial two miles are kept clear by rowers, paddlers and the 32-seater cruise boat which hooted past us with a lone passenger tapping at his phone. But nothing bar the Solent breeze stirred the canal west of the B2201, allowing the thick Sargassian spinach to fester and choke navigation for even the pluckiest of mallards. A picture from 2008 (above) shows less weed at the bridge and a rather squeezy thrutch through a spider-clogged culvert under the road.

Abandon Plan B all ye who Venture Flex here. Austin called in an Uber: ETA 4 mins; ET back to his Volvo: 6 mins. Total elapsed recovery time: 16 mins, give or take. The internet of things – how modern! Soon the hardshells were lashed to the roof and the rolled-up IKs heaved into the spacious boot of the Swedish landraft with class-leading crumple zones.

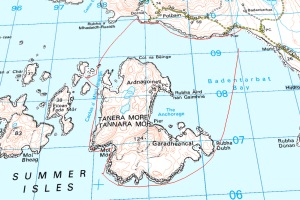

A quick map check and I proposed Plan C: Pagham Harbour just down the road and out of the rising southwesterlies. I’d never heard of this medieval-era port which was now a bird sanctuary-cum-sludge repository, but Elliot had been spotting here so knew the way to the chapel at Church Norton, thought to be the mythical 7th-C source of the overdue Christianisation of pagan Sussex.

A 5-minute haul led to the shore, except the tide – which should have turned over an hour ago – was still way out, leaving only snaking channels accessible down muddy banks. We ate lunch, waiting, like Al Gore, for sea levels to rise. But when the time came nothing but irksome clouds of marsh gnats stirred as we padded over the springy salt-scrub to the nearest channel (above).

All around, collapsed jetties, concrete groynes and other arcane structures recalled Pagham’s 19th-century heyday. Back then the sea had been successfully sealed off and the land reclaimed for farming until a storm in 1910 broke through the embankment, reflooding the harbour for fair and fowl.

Another portage over a shingle bank got us to the main outlet leading to the sea and where the water was rushing out when it should have been filling. I realised that narrow-necked inlets like Pagham Harbour act like reservoirs, releasing their tidal fill gradually for hours after the sea tide has turned. In the tropical fjords of northwestern Australia’s Kimberley it can produce bizarre spectacles like the Horizontal Waterfall (left).

We drifted and boat-hauled through a strange, desert-like landscape of barren shingle banks speckled with forlorn fishermen and demure nudists until the spit spat us out into the English Channel like five bits of unwanted, flavourless chewing gum.

According to images and video on Save Pagham Beach (left), it’s staggering how fast the spit has grown once shingle management ceased around 2004; part of a new ‘natural coastline’ [money saving] policy. The spit has repositioned tidal erosion eastwards and along the shore, accelerating the scouring of Pagham’s foreshore and endangering the homes immediately behind. Recutting the Harbour’s outlet to the west (bottom picture, left) is thought to be a solution, but may transfer the flooding risk inside the harbour. Add in the protected SSSI status of the Harbour and the ‘homes vs terns’ debate becomes complex. Who’d have thought we just went out for a simple paddle.

Eastward along the coast, the assembled infrastructure of Bognor Regis rose from the horizon, while behind us the promontory of Selsey Bill kept the worst of the wind off the waves. With a helping tide and backwind we bobbed with little effort in the swell which gradually grew and started white-capping once clear of the bill. But as I often find, a sunny day and not paddling alone reduced the feeling of exposure and imminent watery doom. Only when a stray cloud blocked the sun for a minute did the tumbling swell take on a more malevolent tone. The buoyant Twists – hardly sea kayaks – managed the conditions fine and the lower, unskirted Ventures only took the odd interior rinse.

Talking of which, All Is Lost (right) was on telly the other night. Lone yachtsman Robert Redford battles against compounding reversals in the Indian Ocean after a collision with floating cargo container wrecks his boat. A great movie with almost zero dialogue.

Just near Bognor all was lost for real (above and left). Only a fortnight earlier, a similar, lone-helmed sailing boat had lost its engine and unable to sail, drifted onto Bognor’s serried timber groynes. Less than two weeks had passed and already the hull was now cracked like an eggshell and the masts were gone (maybe removed). But unlike the doomed Redford character, on the day the Norway-bound sailsman had been able to scramble ashore.

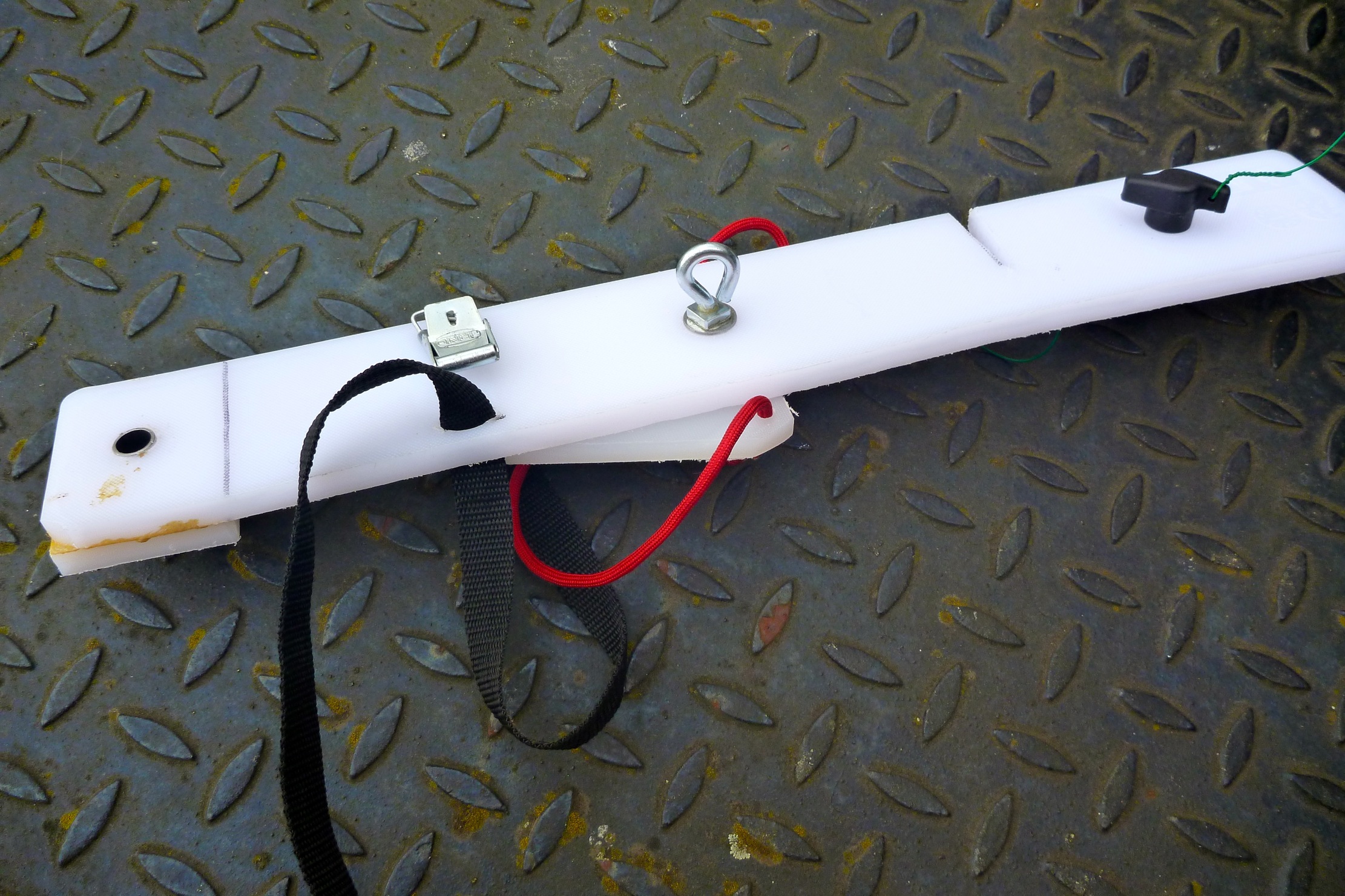

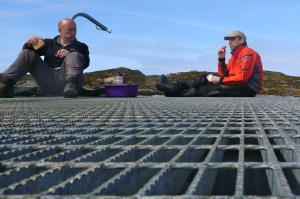

These groyne stumps – designed to limit longshore shingle drift – could also be a bit tricky in a hardshell if the swell dropped as you passed over one. And just along the shore was another wreck (above) protruding gnarly, rusted studs which may well have sliced up an IK. Mostly submerged when we passed, some post-facto internetery revealed it to be the remains of a Mulberry Harbour pontoon, one of many built in secret during WWII as far as northwest Scotland, then floated out on D-Day in 1944 to enable the sea assault on Normandy.

Our own beach assault ended at the truncated remains of Bognor pier, proving the sea eats away at this whole coast. Bognor is a step back to Hi-de-Hi! Sixties Britain when we did like to be beside the seaside. All together now!

So ended a great day of paddle exploring. Uber!